Activities for people with dementia

From a favourite hobby to coffee with a friend, activities can help someone with dementia stay socially active and engaged. Enjoying things that make their life meaningful and pleasurable, like art or nature, religion or spending time with loved ones, keeps their mind busy and help them stay healthy and positive.

Here are some tips to help you plan for and make activities simpler, more relaxed and enjoyable for both you and your friend or family member.

Planning activities

Create a plan for activities to keep things consistent, especially if multiple people are caring for the person. You can also write down what calms them or distracts them if they get upset while doing an activity.

When you’re planning activities for someone living with dementia, choose ones that:

- keep their skills active

- make up for things they might not be able to do anymore

- make them feel good and confident

- help them learn new things

- bring joy, fun and time with others

- respect their cultural or spiritual background

- relate to what makes them special: their job and skills, hobbies they enjoy, things they do for fun, places they’ve travelled or important moments in their life

- make life meaningful, fun or peaceful

- help them stay social. for example, spending time with family and friends, joining community groups or clubs, or sharing jokes or funny moments.

Pick times when the person feels at their best for an activity. For example, morning walks might be better than later in the day.

Choosing a variety of activities

Look after their mind, body and soul by incorporating a variety of activities. Not only are these activities good for their mood, but they can help with physical health too.

- Try encouraging the person to stay active, as exercise releases feel-good chemicals in the brain. Go for a walk or get gardening. Play golf, bowls or tennis, or attend an exercise, yoga or tai chi class.

- Keep the brain active. Your friend or family member might enjoy reading, playing cards or apps, or doing word games, jigsaw puzzles or maths exercises.

- Get creative through hobbies like knitting, painting or playing music. Encourage them to go back to an old hobby, or find a new hobby.

- Try activities that prompt positive feelings or help a person recall treasured memories. Some ideas include: looking through old photos, memorabilia or favourite books, or singing favourite songs. Pets can provide an emotional outlet as well.

- Include sensory experiences. Listen to music, visit a herb garden, brush their hair, or consider a hand, neck or foot massage, if it’s appropriate.

Setting up a safe activity space

People with dementia may find it hard to see or move well, so look to create a safe and comfortable space for activities that:

- keeps things tidy

- reduces noise

- has good lighting that’s not too bright

- has comfortable seating

- keeps things at the right height

- is free of things that can break easily.

Keeping activities simple and easy

When doing something with someone who has dementia:

- let them take their time. Some days, they may not like the activity. Try again another time

- focus on one thing or instruction at a time

- make tasks simple and easy. It’s okay to keep activities short

- start the activity together. Sometimes just being together is enough

- make a photo book to help them remember the fun things they do.

If you notice the person is finding an activity tough to do, there may be ways to make it easier. Here are some ideas:

- If cooking is hard, offer to help. Peel veggies or set the table, for example.

- When you’re playing a game, get someone else to help keep score. Or don’t keep score at all.

Webinar: creativity and dementia

Creativity is for everyone, and can give people living with dementia opportunities to get in touch with and express themselves. In this video, A/Prof Helen English and creative engagement specialists Maurie Voisey-Barlin and Margaret Rolla talk about how to use creativity as a tool to connect and engage.

Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Creativity and Dementia. Dementia Australia.]

Helen: Hello, everyone. My name's Helen English, and I've got the great pleasure today of talking about a topic dear to my heart, creativity and dementia. But first of all, I'd like to pay my respects and acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which I'm lucky enough to live and work. That is the Awabakal people - I actually live near Lake Awaba which is a beautiful lake - and I'd also like to pay my respects to Elders past, present, and emerging, and also to any Elders past, present and emerging on lands where you live, or any Aboriginal people watching this webinar. I thought I'd start by giving an outline of my talk so you know what to expect.

First of all, I'll be talking about creativity. What is it? Almost impossible to answer, but good to think about. Secondly, I'll be talking about the benefits of creativity for older adults, generally. Thirdly, I'll talk specifically about benefits for people with a diagnosis of dementia. And then fourthly, I'll talk about some key aspects that help to bring wellbeing effects when you are engaged with creative activities. And then, during the talk, we're going to hear from two amazing people who work closely with people with a diagnosis of dementia in different creative forms. And finally, I'm going to point you towards some resources and programmes that you might like to look into.

First of all, what is creativity? I think we all agree that human beings are inherently creative, and creativity is not just the realm of the artist creator, a person who dedicates her or his life to producing works of art. No, creativity is also an everyday activity and ability. We use creative thinking to solve problems. Imagine different scenarios, make and change things, and so on. As Alfred Einstein famously said, imagination is more important than knowledge for knowledge is limited, while imagination embraces the whole world.

To help us understand different levels and uses of creativity. James Kaufman, an American psychologist who specialises in creativity, has come up with four types of creativity, which represent a progression and a development - from mini C to little C, to pro C and big C, where the C stands for creativity. And this ordering of creativity is useful to break down commonly held beliefs that only a small percentage of the population can be creative. For these four, mini C refers to everyday creativity. It might be a thought or an insight, not shared, but used to make sense of our worlds, to imagine possibilities and think around problems. Little C represents the step from an idea in our heads to an articulated concept that we might share with others. Pro C is a professional level of creativity, and big C covers a genius level.

So, what are the benefits of creativity for older adults? And this is something that I think about a lot, because I work with older adults and my topic is creative ageing, so I'm lucky to work in that area. The creativity is beneficial as we age, and in fact, we become more creative as we age. And this has been suggested for over 20 years, however, was established in research by Areeba Adnan and Roger Beaty in a study of older and younger adults, that the older group being around the age of 70, and the younger around the age of 20.

And using FMRI scanning, they observed that in divergent thinking tasks, which are used to measure creativity, the older adults showed in experiments that they call on imaginative thinking, in tandem with logical thinking to problem solve, and to perform a task. For example, listing all the possible uses for an object such as a brick. This is a standard divergent thinking test. So, from this, Adnan and Beaty demonstrated that in older adults, the imaginative network, which is also called the default network, is more strongly coupled with the executive or logical network during creative thinking than in young adults.

We can consider that this may be an adaptation to ageing, where we draw more readily on the amassed knowledge and experience of a lifetime. Therefore, we should explore and develop this later life strength, and take the courage to delve into both everyday creativity, and to explore our creative potential through engaging in creative activities. Further, there's a strong link between being creative and having an open mindset, and having an open mindset is a key aspect of ageing well, because it means we are more likely to seek solutions to the challenges of ageing. So what are the benefits of specifically engaging in creative activities, such as painting, joining a music group, or taking up a craft for older adults generally, and for people with a diagnosis of dementia specifically?

An important underpinning factor to mention first is that creative activities do not depend on memory, but have the power to evoke memories. Thus, people with a diagnosis of dementia and memory challenges can participate, and may benefit from a return of memories as a result. And this may, in turn, facilitate communication with loved ones, reinforce a sense of self, and support relationships with family and carers. Many of you may have seen the well-known documentary, Alive Inside, if you haven't, do look for it. In this video, someone who is usually very withdrawn and non-communicative hears music from their youth and becomes very excited, literally seeming to wake up, and begins to talk about the music that he is listening to. Moments like these stimulate compassion not only in the person's family, but also in professional carers, and therefore, have potential to improve not only the participant's quality of life, but also those around that individual.

What are the benefits of creative activities? Well, first of all, they are enjoyable. We experience positive emotions for engaging with the arts, whether painting, singing, dancing, or crafting. And positive emotions have been shown to affect cognition and wellbeing. Second, engaging with creative activities gives us a sense of control and purpose. Third, we have a sense of achievement through acquiring new skills and finishing a project. And fourth, we can share the final product. So for people who are gradually losing control in their lives due, perhaps, to diminishing physical health, cognitive issues, mobility challenges, creating something can bring back a sense of agency and control. When making art, they're given opportunities to make choices, where these are not so evident in everyday life.

I recently watched a video of an artist working with a person with dementia on one side, and their carer on the other. They were all working on the same project, yet, there are always choices, and the person with dementia chose to work with strong horizontal lines rather than free flow shapes. So, it doesn't matter what your choices are because everything is acceptable, there's no judgement in making art. Each follows their own aesthetic and each enjoys their different results. Being engaged in creative activities is a way to engage with emotions, whether experiencing them because of the creative process, or expressing emotions through the process. And it is good to note here that the process of making and creating is often more important than the outcome.

Feeling and expressing emotions gives us the opportunity to share and manage them. For people with dementia who may be challenged to complete an artwork, researchers argue they can still get benefits by expressing emotions and feelings through engagement in the activity. Further, research by Barbara Fredrickson shows that experiencing positive emotions broadens an individual's scope of attention and cognition. And her research highlights that creativity specifically increases with positive emotions. So, a lot of good things about positive emotions to note that. Importantly, arts and non-verbals will create a level playing field in terms of communication. People with dementia are often withdrawn, which may be linked to their perceived inability to communicate verbally. But when participants feel the space is safe, they have the opportunity to communicate through art making, and this may bring them out of themselves.

In a safe space, people can also be playful, living in the moment and responding to others or the art process. We'll hear more about this from Maurie Voisey-Barlin later. Arts provide a topic for conversation, a focus point with significant others, which is not related to the individual's dementia diagnosis. The creative activity and the products become the focus, rather than the dementia itself. Arts activities are stimulating, and participation is, therefore, fun and potentially relaxing for carers as well as the person with dementia. In addition, group art activities provide social context and mitigate against the isolation of dementia.

The person with dementia and loved ones can participate together in an activity that creates its own space, and is something of a refuge for its duration. Research shows that people with dementia may have benefits to behaviour and communication as a result of engaging with creative activities. For example, engaging with creativity may have a positive effect on mood and calm agitation. This is well documented with music. Although creative activities are non-verbal, they can also revive language, and there are many records of the return of language and communication continuing, even after the activity is over.

A second probable factor in stimulating communication is the access to memories that creative activities can evoke. So next, we're going to hear from Margaret Rolla. And Margaret is now based in South Murwillumbah, New South Wales. She's a creative ageing specialist and Director of ArtIntuit. Margaret now helps individuals and aged care providers who are looking for meaningful activities to engage and alleviate the boredom, loneliness, and symptoms associated with grief, loss, ageing, and dementia.

Margaret: Thank you, Helen, and a big hello to all our viewers. I'm really excited to share some of my work with you today as a creative engagement specialist. As we've already heard from Helen, creativity is so important for health and wellbeing of all people with all ages. My belief, though, is that being creative isn't a privilege, it's a basic human need. And having the opportunity to create is a human right. I support the emotional needs of older people, and those living with dementia through meaningful art making, using drawing as a tool of discovery. I'll be showing you, today, some simple practises that you might be inspired to tap into your own creativity, or within those you care for.

So why drawing? Well, drawing is primal. It's mankind's most basic form of communication. We drew before we could speak, but drawing also uses both sides of the brain, so it's cognitively stimulating. What I've found in my work though, is that it also assists with gross motor skills, and it strengthens hand to eye coordination. Drawing is natural, it's simple, and it's easy to instigate, and it can be done with any tool on any surface, within reason, of course. So, how do we tap into this creativity? My recommendation is to tap into their history first of all. Memories can inspire art making through the use of photos and printouts, but it can also generate the imagination too. Our memories can be true, or we can make new memories through our intuitive thought system. A person living with dementia does not lose their intuitive self and felt sense of experience.

Through my work in aged care, I've developed the four E's of engagement strategy, which may help kickstart the creative juices of those you care for. They're only suggestions based on my learnings. So the first E is the environment. Choose a quiet, non-intrusive, specific area to assist their memory. Let them mark their territory with their artworks. Treat the space seriously though, there's nothing worse than a focused resident being pulled away from creating, to be asked if their bowels have been opened that day.

The second E is exploration. Focus on the process rather than the outcome, because that's where the juicy bits lie. And try a variety of tools and media, and just simple mark making activities is enough. Offer suggestions and offer choices. I had a client who used their morning tea as inspiration, and strategically placed four pieces of her cake on each corner of her drawing. It was really beautiful. Just beware though, the paintbrush dipping into the coffee cup though.

The third E is expectations. People living with dementia need time to process their thoughts and digest instructions. Give them time, give them silence. There's no need to chatter during the art process. Expect the unexpected and embrace it. Expect resistance, so have a backup plan in place. The fourth E is excitement. Add music. I can't advocate this enough, but choose music that is relevant, meaningful, and appropriate to the person and their mood that they're in on that day. Let the music inspire art making. Draw the music, but join in and create together. Inject humour and laughter. Maybe do some movement, dance, make a mess, or simply just sit there with them quietly and enjoy watching what unfolds.

Remember that patience, persistence, and respect promotes dignity. So never take over their work to finish it. You can start off with a few lines and marks to help them, even guide their hand, but please don't finish it. Admire the outcome for what it is, an exploration of line, shape, and colour, and it's an intuitive felt sense of experience for them. And remind them too if they're being critical of their work, which they most often are. So what materials and media to use? I say mix it up. This allows freedom of choice and exploration of a variety of textures and colours, to sensory experience. What is accessible to one, though, may not be for another.

Why not try digital technology? Computer tablets have mixed reactions, but they do provide a solid surface and a defined boundary, and this is really good for sight impaired people especially. A client of mine, who was stroke impaired, found the tablet easy to manage with her non-dominant hand, where holding a pencil was very uncomfortable. It also encourages conversation and connection with families, particularly grandchildren. But no special tools are needed to create interesting marks and abstracts, look in the kitchen drawer, and in the backyard, you'll find something to draw with. If you purchase cheaper brands of materials though, I recommend removing the label, or covering up the word 'kids' from the label, this promotes dignity again. But overall, try something new. Think outside the paint box. This is just skimming the surface and I'm still learning from my artistic Elders. If you want to learn more, you can check out my website for more resources and amazing stories, but thank you for listening. Bye now.

Helen: So, my next point is what is important to consider when we try to make creative activities effective? So there are three things here, although the second two are very closely linked. So, there's engagement. The activity needs to be person centered and also co-created. But positive benefits in engagement is really the key element. The activity needs to be something participants enjoy and can relate to. Some researchers argue that the engagement with the activity is the most important aspect. It seems probable then that the intensity of engagement is what stimulates some return of communication and even speech.

So the second factor person-centered approach, this is very important, and we're going to hear more about it in a moment from Maurie, and it is linked to co-creativity, or co-creation. So, person-centered creativity works well even into advanced dementia. This approach uses improvisation to create a conversation through movement, gestures, touch, and sounds. This creative and improvised conversation is the essence of co creativity. The concept is to elicit responses using these means, and is often led by engagement therapists who use clowning. So we're now going to hear from Maurie Voisey-Barlin, who is a creative Elder engagement specialist. So now, it's my pleasure to introduce Maurie Voisey-Barlin, and Maurie is based in the Hunter region of New South Wales, and he's an engagement specialist who works with elders in residential aged care.

Maurie: Hello, my name is Maurie Voisey-Barlin, and I'm a creative therapeutic elder engagement specialist, which is a big mouthful, but it tries to encapture what I do. So, my role is to engage people who are living with dementia in residential aged care, with a focus on those that are living with grief or depression, or are choosing to self-isolate and socially withdrawing themselves from general activities and engagement. This could be related to their dementia; it could be related to their comfort or discomfort in residential aged care. This could also be fear around engaging with people. And when we are at our loneliest, we tend to push people away. So, my role is to get into the room, and engage them using history, personhood, individual interests, and to create curiosity so that I can draw them into relationship.

I would see around about 80 elders a week in one-on-one sessions. And these are the same 80 people that I build a relationship with, over seven sites throughout the Hunter Valley here in Newcastle. What I want to talk to a little bit today is to look at well, whilst I'm working in residential aged care, I think the application of what I'd like to talk about is the same for us who are care partners with people living with dementia in the community, at home, or in respite, or going into residential aged care. So what I want to talk about is looking at, rather than using the idea of conceptual engagement, I want to look at tangible.

To explain this, I've got a few photos I'd love to show you, and let's begin. Here, we have a good friend, Lee. Now, Lee lives in a dementia specific unit or memory support unit, whichever you would like to call it. And Lee is really engaged through music. Now, I use music quite a lot in my work, but I would say that it would be only 50% of my work. What I'm using is performative skills. So, I have a history as an actor, and I'm looking at improvisation, storytelling, yarns, banter, and of course, creating relationship, but music can play a large part in that with some people. I would not use any music, but with Lee, Lee has a great fondness for the song "Pearly Shells". And here I am, following Lee's lead. He sings the first line, and I repeat the line as I play it on the ukulele for him. So, this is a musical intervention, but of course, we go into relationship very quickly, and I've been engaging with Lee for probably around about four years now.

In terms of music, there is another musical intervention, which is probably would be seen as purely musical, but I'm actually working very deeply here with Laurel, my elder buddy Laurel here, who used to play the piano accordion. And there's some footage which I can share a link to, filmed by her son. So, Laurel loves old time music and it activates her. I use music to activate my elders. And in this sense, then I can start to engage Laurel using phrases, a cheeky banter, and interaction, and she'll pick up my social cues. Whereas prior to me seeing her each day, she would sit in her largely in her own thoughts and would not be able to construct words or sentences. Here, you see her wearing my hat, which she wanted to wear as part of the session.

When I say tangible, what I'm talking about is rather than talking to my friend Terry here about his beloved Penrith team, I'm actually taking photographs of the Panthers for him, but here, I was teasing him, trying to convince him to come back to Parramatta because I know, through my research, that he used to support Parramatta before Penrith, because Penrith came into the competition much later. And with that knowledge, and that looking back, I'm able to find out who his original team is. So here I am trying to show him a picture of Peter Sterling and convince him to come back to the fold.

So, the idea of using a tangible object, or a picture, or a painting, using photographs, it kind of does the work for you, and it's an invitation to engage. And it takes it away from the concept of talking about a photo of me as a baby, but rather presenting a photo of me as a baby. Here, I'm showing Loretta, or I had shown Loretta a photo of me as a baby, she didn't think it looked like me, so I flick over and I have one drawn on with a beard, although it does look like I drew it right there.

This is my mentee, Chloe. Chloe is a volunteer who comes with me every Tuesday, and has done for nearly two years. And here she is showing our friend Baz, who loves mischief, and the absurd, Chloe is using a picture of her dog on a skateboard. So, bringing in that photograph and showing him this picture, which he finds really amusing. Same here with my friend Norma. Norma used to say every day, "I'm sorry, Maurie, I'm in too much pain." And looking at the history, I noted that she loved textiles from foreign countries, as she called it. And so, I started to drape this Thai silk scarf, sorry, a Lao silk scarf around my neck, or a llama wool bag, and I would wear this in, and then I would validate her feelings, and accept that she wasn't able to see me, and then I'd go to leave when she looked at it. And sure enough, I'd say, "That's a shame, I would've loved to have asked you what this material was." And very soon, she would start to take note and feel the scarf, and before I knew it, we would be able to engage. So rather than talking about textiles, it's about placing them in someone's hand or in front of them so they can actually feel the material.

Finally, sometimes, some people like to ask me for a photo, and my mentee, Chloe, made this one up for me, so if they ask for a photo of me, I usually will give them this one just for a bit of fun. There is so much more to talk about, but obviously, there isn't the time. But I can supply some links to some of my work if you're interested in reading about some of the engagement strategies I've used, I really love to share what I do in the hope that others may take inspiration from it, or start discussion about how we might engage our elders living with dementia in our community and in residential aged care.

Helen: So, thanks Maurie, for your amazing contribution. I'm now going to talk about some resources and just draw your attention to some possible resources you might look like to look into, and I've got a list of those on a later slide, but I was just going to highlight a couple, so one of them is pressing nature into clay, which you can see at the top right of that image there. So, this is where working together, people can collect leaves and other plant material, and you press that into clay. But firstly, they need to roll out the white clay.

The activity can be extended, if it's a fine day and people can go out and collect leaves themselves, otherwise, you can bring them in. It is very simple, but very, very, looks really beautiful. So it gives a great result. So you press the leaves into the clay and then paint over them, and let it dry. And you can paint again later after you've removed the leaves if you want.

And that is in a resource, which I'll show in a minute, and also in the same resource is one called Concertina Houses, which is just a shadow representation of that in the bottom right of the screen. And that's where you may have done this when you were young, where you fold up a piece of paper and then you cut a shape. And that is echoed through the whole concertina effect. And in this one, you cut out a roof in a chimney and then you ask people to, or you do it with your partner, to put some images down that are important about one of the homes that they lived in that's got a strong memory. And they can also decorate the other houses in the Concertina shape with things, memories that come back. And then, the really lovely thing about this one is that you can then use that as a starting point to share memories in a group, and talk about why those memories, and what else comes up with that.

Just to finish up, for fun, I'd like to share this very short video, which comes from Crossroads Hospice and Palliative Care in the United States, and the reason I really like this is because there there's no text, there's no words. You just watch it, and you know what to do.

[Video Plays]

And so, here's a slide showing you some of the places that I found for you to look for more activities, and you'll see Postlethwaite, Liz, this is supported by the Baring Foundation in the UK, which is a fantastic charitable organisation. And that's the one where there are a lot of these ideas that I just shared. And the last page is references, and thank you everyone for watching, and thank you very much to Maurie and Margaret for contributing, and to Gina for helping make this webinar.

[Title card: No matter how you are impacted by dementia or who you are, we are here for you.]

[Title card: Dementia Australia. National Dementia Helpline 1800 100 500. Dementia.org.au]

[END of recorded material]

You can find the beautiful video of Laurel that was mentioned in the webinar here: OPAN Covid-19 Webinar: Laurel dancing.

Tips for enjoying art and writing together

Creating something is a joy. The person you are caring for may have enjoyed art or writing previously, or this could be a new activity for them. Here are some tips to help you get creative together:

- Set up: Find a comfortable table and gather art supplies like paper, colours, pens or clay. Let them choose what they want to use. Invite them to join but don’t push if they're not interested. You can always try again later.

- Get inspired: Keep things like shells, flowers or photos nearby. These can inspire them. Describe the items to spark memories or ideas.

- Start together: If they need help, start the activity by choosing colours or drawing the first lines. But if they’re used to this, they might not need any help.

- Help with writing: Writing might be enjoyable. You can help by using photos to start a story or by writing down what they say. Ask if they want help or want to do it alone.

- Support their work: Be encouraging about their art and writing. Admire the colours or patterns. Treat their stories as creative pieces, and don’t worry if words are misspelled. Read the stories out loud.

- Show their work: Respect what they create as their expression. Ask them to sign it, and then:

- put it on colourful paper

- make a card out of it to send to family

- frame it.

Tips for enjoying music together

Music is relaxing. It can encourage fond memories and feelings of calmness and security. It can be a useful distraction from stress, and can help settle someone who is living with dementia. Here are some tips.

- Relax and listen: Music they're familiar with may help to relax them. Try YouTube videos of their favourite artists, radio, music streaming or CDs.

- Focus on familiar tunes: Music from their childhood or early adulthood might resonate the most. Find songs or tunes they loved back then. This could include music from a specific artist, religious songs, nursery rhymes or music connected to meaningful times in their life.

- Sing together: Sing along to familiar tunes, with or without music. You could sing with your friend or family member while you’re doing everyday tasks like washing dishes or taking a shower.

- Move and dance: Move or dance together to music. You don’t need to be an expert dancer—just have fun moving together. Sway side to side holding hands, or dance if they used to enjoy it.

- Invite others: Ask friends who sing or play instruments to visit. Kids in the family who love music can join in too. Clapping, tapping feet or using simple musical instruments can get everyone involved.

- Concerts or music groups: Check out concerts or music groups they might like. Contact local community centres or music groups to see what events are coming up.

Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Dementia Australia]

[Title card: Music engagement for people living with dementia]

Geena: Hello, and welcome to today's presentation on music engagement for people living with dementia, where we'll be exploring how you can use music for health and wellbeing at home. I am Geena Cheung, a registered music therapist based here in Sydney. I'd like to start off with an acknowledgement of country. I acknowledge the traditional custodians of country throughout Australia and recognise a continuing connection to land, waters, and community. I pay my respects to them and their cultures, to Elders both past and present, and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples viewing this video today.

So, what is music therapy? Music therapy is intentional use of music by university trained therapist who is registered with the Australian Music Therapy Association, also known as the AMTA. Music Therapists draw upon evidence-based interventions that aim to improve quality of life. And it differs from music education and music entertainment because the focus is on health and wellbeing.

I'd like to start off with a short introduction on music, the brain, and everyday life, and how that all relates to one another. So receptive and active music participation stimulates the whole brain as depicted by this little image in the corner. It's an integration of motor, cognitive, emotional and sensory processes, and because it engages all those things simultaneously, it has the ability to induce neuroplasticity. That is the brain's ability to regenerate in the face of deterioration and damage.

Now, music can also alter our emotional and arousal states because it triggers the release of different chemicals in our brain, and can also affect the way we breathe, and the rate that our heart beats. And lastly, music is associated with time, place, people and events because we often use music in daily life to accompany activities, or for social bonding and et cetera.

Well, today we'll be looking at a bunch of activities as well as their outcomes. The activities that we're looking at include music listening, singing, rhythm-based activities, songwriting, and music and relaxation. We'll be exploring how you can use these activities at home and I'll be providing some tips, as well.

Starting with music listening. Music listening is a meaningful way to pass time. As we saw earlier on, as it does stimulate the whole brain, it makes it a great activity to engage in passively but also containing therapeutic benefits. If you're sharing a music listening session with someone, you can use music as a starting point for conversation, which leads to social bonding. You may also like to use music to accompany activities of daily living, such as personal hygiene activities, mealtimes, or even movement to music.

When I say movement to music, I refer to general exercise that you may enjoy doing, such as going for walks, or else it could be physiotherapy exercises that are quite repetitive. And if you're someone that enjoys dancing and having a bit of fun and expressing yourself, that's also something you can do to music. When we perform movement to music, we naturally sync up with the ongoing beats of the music. And this is the process of entrainment, where entrainment is a timed structure of two or more systems that become synchronised. And this naturally happens because as I mentioned earlier on, music can affect the brain, and therefore, can affect the rate at which the neurons are firing and leads to our motor actions becoming synced up with the music.

Listening to music can increase connectivity in the brain, as I mentioned earlier on, it's also a positive shared experience that supports social bonding, if you do it to other people. It can enhance the experience of activities of daily living if you select the right kinds of music to support the activities. And lastly, it improves psychological wellbeing by enhancing mood, inducing relaxation, inspiring reminiscence, and maintaining self-identity if you're listening to music that you've always enjoyed in your whole life. And some tips on using music listening at home. Therapeutic benefits are augmented if you use the music that is familiar and meaningful to the person. And, again, if you select music that matches the energy levels and mood of the personal activity, that again, increases the therapeutic benefits of music. You’ve got to be careful about music that changes erratically as this can cause agitation at some times, so be really careful with the radio. Finally, music can provoke negative feelings and memories so always monitor the emotional response of the person listening to music.

If you require more resources on how to create your playlist for therapeutic music listening, or else you just want to learn more about the benefits of music listening on health and wellbeing, you can head over to playlistforlife.org.uk, where there will be a tab called “Make a Playlist”, and many free resources that you can download such as this little template prompt that will prompt you to think of songs that are attached to memories.

The equipment you may require for music listening include your personal CD or records collection, or else you can create playlists on streaming platforms such as YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Music, and so on. Or else you can create playlists and pop them onto an MP3 player like this one. The benefits of creating a playlist is that you can tailor them to particular activities. You may end up with a playlist for your active exercises, and another playlist for cleaning, or another playlist for going to bed, and so on.

The next activity we'll be exploring together is singing. This is highly accessible because you can do it anytime, anywhere, and you don't require any equipment at all, if you don't have any. It includes singing familiar songs with and without music accompaniment, or you can improvise, and make it up on the spot, and express yourself. If you are doing singing together with someone, you can encourage participation by leaving out the final words at the end of the phrases. For example, "You are my sun, my only sun, you make me ... When skies are ..." Just like that. When you couple singing with active movements such as clapping, you're exercising dual tasking, which once again, lends to that neuroplasticity in our brains. It also helps ground singing when we're singing without accompaniment. For example, "You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy ..." I think the clapping leads to fervour and motion, and also, it just really helps give it a time reference on rhythm.

The benefits of singing include the maintenance of executive function such as attention, regulation, adaptive thinking. If you are sharing this activity with another person, it's social interactivity. It can help you maintain speech and language ability as well because when we sing, we often use words as well. And it improves psychological wellbeing because it enables emotional release, enhances your mood, and because you're expressing yourself through using your voice, it's self-expression, which helps maintain or else increase self-confidence.

Our next activity is rhythm-based. So, we have four activities listed here. The first one is free drumming which is kind of self-explanatory. You just pop on your favourite music that really gets you going, and you just drum away however you want. Our second activity listed here is maintaining a basic beat. Again, very self-explanatory. Pop on your favourite music and just follow the beat. You'd be surprised even such a simple action requires a lot of planning – we're listening to the music, we're processing the beat and what's going on, and then we're organising and coordinating our motor and auditory systems to create an action that is also relevant to the ongoing stimulus. And if you want to take it up the next level, you may like to try some patterns.

There are two ways of making patterns. The first way is making rhythmic patterns, like this. And you can try this activity by taking turns with a partner. The second way of making patterns is making sequential patterns and this is just a series of different actions, or you may like to explore different ways of playing a drum such as tapping your fingers, knocking off your fist, smoothing with the palm and rumbling, and using that to make a sequence. You can also make sequences by varying left and right hand. And as I did earlier on, I incorporated my body parts. The benefits of rhythm-based activities are very similar to therapeutic singing, mostly because they're both activities that are active music making.

So, here, we have improved cognition with the addition of benefits to memory and planning, especially if you are using patterns. Once again, if you're doing it with someone, then you're engaging in social interactivity, and it improves psychological wellbeing much like singing. Some tips, you may have already heard me mention it a few times but it's quite fun to do it with a partner, and enabling turn taking where possible is a great way to just interact. You may also like to include concept as fast and slow, or loud and quiet, to exercise cognitive flexibility and regulation. So you may go, “Okay, fast, or else slow”. And we can use body language to communicate this such as fast, slow, loud, and quiet. Those are my ways of using body language, you have your own, I'm sure. The equipment you may need for rhythm-based activities include anything that makes a sound at home – you can use your body, body percussion is a thing. Just make sure you don't hit yourself too hard, otherwise you’ll go a bit red. Or else you can purchase small instruments from your local music shop. These little drums come for about $90 and they're very small. Or else you can get a little tambourine with a drumhead on it, and these range between $10 and $20. And the benefits of a tambourine for a drumhead is you can shake it, and you can also hit it.

Our second last activity we're exploring today is songwriting. A lot of people feel a bit nervous about approaching songwriting but it doesn't have to be anxiety inducing. If we simply change the lyrics to existing songs, it makes it quite accessible activity for anyone to try. And you can engage in lyrics substitution in songwriting by reflecting on the main message or theme of the lyrics, and then creating your own lyrics that fit the melody and the theme. Let's try an example. I'm sure we're very familiar with this song made Famous by Louie Armstrong. It goes, "I see trees of green, red roses, too. I see them bloom for me and you. And I think to myself what a wonderful world." And this can lead you to reflect on what you think is wonderful about the world, and you may like to make a list, and then construct sentences that fit into that melody.

Use visual prompts were appropriate. Photographs are great way to really help you record those memories, or prompt your thoughts, and you can create songs to help learn and remember important information, as well. For example, if you keep forgetting someone's phone number, just turn it into a song, and it's a great way to learn because our brains naturally encode that information easier.

The benefits of songwriting include improved psychological wellbeing. If you're participating in this activity with someone else, it leads to social bonding through a discussion and sharing memories, thoughts, and feelings. It inspires reminiscence and this is the reflection on lived experience. It allows you to express your thoughts and feelings, and because you've completed something creative, it leads to a sense of accomplishment.

The final activity we'll explore is music and relaxation. When we use music for relaxation, it helps set up a space for us to really downturn our nervous system. It also helps create timeframes for us to time these relaxation activities. For example, if we're doing mindfulness to music, it might be a good way to think of it as, "I'm going to do this mindfulness activity until this song ends." I've suggested two mindfulness activities here, but I'm sure you can find more or you have ones of your own that you're already practising. So, great mindfulness activity to do through music is simply belly breathing which requires no equipment and can be done anywhere, any place. You just pop on your music, close your eyes if you feel safe, and just allow your breath to flow in and out as you listen to the music. If you're looking for a more engaging breathwork exercise, you may like to try box breathing or the 4, 4, 4, 4 exercise where you breathe in for four, hold for four, out for four and hold for four. Once again, because of entrainment, we'll naturally start breathing in time with the music and holding our breath in time with the music.

Finally, a mindfulness activity that you may like to try. People usually like to do this one before bed, especially if they have trouble sleeping. It's a body scan. It's simply where you scan your body from head to toe, one part at a time, and relaxing them or the other way around, toe to head. Some people prefer guided body scans, and this, you can access through CDs that you may find at the library, or else online.

A more active way to relax if you're an active relaxer like I am, is art expression to music. This may include drawing or painting to music. Drawing can simply mean putting a pen to page and following the music wherever it may flow, or else, listening to the music and seeing what comes to mind, what images are inspired or memories, as well. Painting can include splashing colour on a page in time with the music, or else similarly, painting what images are inspired by the music, and using colours that are inspired by the music. Art expression can also be buying colouring books from your local bookshop or newsagency, and engaging in colouring.

Music for relaxation is generally slow because that has an effect on our nervous system, and slow music helps slow our nervous systems down. You may even like to use nature sounds, or the sounds of your environment to facilitate relaxation. This leads to awareness. And finally, everyone relaxes to different music, so choose your own adventure, pop on the music that you relax to. Doesn't necessarily have to be classical music, as many assume.

Relaxation is as important as physical exercise, just because it's important for us to help prevent stress and anxiety that we may experience in our daily life. Therefore, doing relaxation to music helps improve physical wellbeing by slowing down the heart rate and lowering blood pressure, as examples. It also helps improve concentration and mood if you allow your brain to have a break. It can help improve sleep quality, because I'm sure we've all experienced at some point when we're particularly stressed or anxious, just makes it so hard to sleep at night.

I'd like to also inform you on how to access music therapy if you'd actually like to see a registered music therapist. You can head on to the AMTA site by following this link that is provided in the resources area, and then you go to public resources tab on top where you'll find “find an RMT”, and this will lead you to a page of the directory, where you can include your suburb and your postcode in Australia, and then you can click on more filters and select specifically what kind of service you would like to acquire. Music therapy sessions can be funded by yourself, it can be funded by NDIS funding and your home care packages, if you have them. Thank you so much for watching my presentation today. I hope you got something out of it.

[Title card: Together we can reshape the impact of dementia]

[Title card: Dementia Australia. 1800 100 500. Dementia.org.au]

[END of recorded material]

Webinar: the Montessori approach to activities and dementia

In this webinar, accredited Montessori trainer Wendy Henderson explores the connection between Montessori and dementia, and the Montessori approach to activities.

This approach is designed to develop meaningful roles and routines, and enable a person living with dementia to function as independently as possible.

Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Dementia Australia]

[Title card: Montessori approach to activities]

Wendy: Hello, I am Wendy Henderson from the Centre for Dementia Learning at Dementia Australia. I am an accredited Montessori for dementia trainer, and have had the privilege of introducing the Montessori philosophy for quality dementia care in many settings. I'd like to begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today. I would also like to pay my respects to Elders past and present, and to our shared futures.

You may have heard about Montessori in a school setting, and therefore, a common question asked is, how did the connection between Montessori and dementia occur? Well, it was based on the originated and original work with Dr. Maria Montessori, the first female doctor in Italy and childhood educator in 1907, who developed an interest in the treatment of special needs children through her work at the University of Rome Psychiatric Clinic. Dr. Montessori developed an interest in working with underprivileged children thought to be unteachable, so provided with the opportunity to study the children, was given a room, and took charge of 54 children of the dirty desolate slums of the San Lorenzo outskirts of Rome.

She worked with these children by preparing the most natural and life supporting environments, ensuring the children had an active and meaningful role in the classrooms, transforming the room given to her into an environmentally specific room tailored to the needs of the children, so that the child may fulfil his or her greatest potential, physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. By learning in a non-traditional environment in this way, the children learnt skills needed to survive and provide for their families that they otherwise wouldn't. For her committed efforts on behalf of children and humanitarian work, Montessori was nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949, 1950, and 1951.

Dr Cameron Camp, PhD, is a well-known American psychologist, specialising in applied research in gerontology. He received his doctorate in experimental psychology from the University of Houston in 1979. For 16 years, Cameron worked in academic settings, teaching coursework in adult development and ageing, rising to the position of research professor of psychology. He is a past director of the Meyers Research Institute, and is currently a consultant continuing his research and training throughout USA and internationally. He has worked extensively with Dementia Australia over many years.

Cameron's interest in Montessori commenced when his children started at a Montessori school in the seventies, at about the same time as his work in gerontology. When he went into the Montessori classroom designed to enable kids to succeed, to circumvent any physical or cognitive challenges, and saw the resources being used, he thought it ideal for persons living and working with dementia. Cameron was inspired by the work of Maria Montessori. Her philosophy was that every human being has the right to be treated with respect and dignity, to have meaningful role in a community, to contribute to the best of their abilities, and to live a life that promotes self-esteem while respecting one's self, others, and the environment.

Dr Montessori did not treat children like children. She treated them like persons. She used the same values of respect, dignity, and her equality in her approach to everything. These are the values of the way we all want to live, how we all wish to be treated. And so, using the Montessori message, Dr. Camp commenced use of Montessori based activities as rehabilitative interventions over many years of working with people living with dementia. He has written books and many journal articles, one of those books being Relate, Motivate, Appreciate, an Introduction to Montessori Activities. This book was written in 2013 when we were still Alzheimer's Australia Vic, and is still available on the internet.

For many years now, this is the way we work with persons with dementia and also how we all live our lives. Dr Camp says, "We always say a person with dementia is a normal person who happens to have a memory deficit, and maybe some problems with function, but if you give them a situation and the supports where they don't have to rely on the deficits, you are left with a normal person." This is what Montessori does. It provides supports, strategies, activities, and roles that enable a person living with dementia to function as independently as possible. Maria Montessori had a quote. "Everything you do for me, you take from me." Often, in dementia care, we care too much, and we do too much for the person. We help them too much, often, due to time constraints or we just want to be helpful, but this takes away their opportunity to do some things for themselves, and often, they do not have the opportunity to care for others either. So, Montessori assists and supports the person to be as independent as possible, can be used as a tool for rehabilitation. For example, designing a program of activities and roles that enables a person to build strength and fine motor skills that may assist them to maintain ability to feed themselves. Montessori can be used and adapted for any setting, and can be used for all stages and types of dementia.

There is always a purpose to the activities and roles. Montessori activities are not just done for the sake of it. There is thought, assessment, and purpose behind them in order to encourage independence. Meaningful roles and routines are based on what we know about the individual's interests and level of ability. The purpose of the activity or role may be to assist with the cognitive skills using activities that promote number recognition, matching items to size and colour, sorting items into like categories. It may be to assist them with their physical and gross motor skills, to encourage independence for activities such as sweeping, exercise, and throwing balls.

Montessori-based activities as rehabilitative interventions place emphasis on an environment that supports memory loss and respects the person. It provides an approach for shaping a purposeful, meaningful community in which a person with dementia can live. It enables individuals to be as independent as possible, to have a meaningful place in their community, to have high self-esteem, and to have the chance to make choices, and meaningful contributions to their community. Montessori can be used as a tool for rehabilitative or restorative interventions. I'd like to make it clear that this is linked to procedural memory. It can be controversial, but that is because people don't necessarily understand that that is the link. Maintaining activities and roles that enables the person to build strength and fine motor skills can be things like assisting with hanging out the washing, squeezing the pegs actually exercises the fingers in the hands, using tongs to serve salad or vegetables, assists to maintain skills to grip a fork or a spoon to feed themselves, gross motor skills to maintain strength in arms and hand, to hold a garden trowel to dig and plant bulbs, or squeezing the nozzle on a hose to water the garden. There is always a purpose to the activities and roles.

What you do to support the person will depend on their strengths, abilities, skills, and interests. Using cognitive ramps and cues, setting up signage and external cues may assist a person to be more involved and independent. We ask questions like where are the cognitive ramps for a person? And how can we modify our homes and communities to better accommodate persons with dementia? Where are the cognitive ramps for a person? Maybe we need signs on doors, or labels on cupboards. Have you got a calendar? The day and date marked? What are some external cues, like clothes on the bed and turning on the shower so they can hear the sound of water? Opening blinds to let natural light in to signal daylight? Being handed a tea towel to dry the dishes, jigsaw puzzles on an uncluttered table to signal a puzzle to be solved, setting up the hose ready to water the garden. Remember, keep it simple. Too many signs will confuse, and too much clutter will confuse.

Now, I will discuss memory to help you understand the why about what we've just spoken about. Our memory is a complex system that has many layers. When considering the impact of dementia on memory, and the capacity a person with dementia has to engage in meaningful activities, it is important to distinguish between declarative memory and procedural memory. Declarative memory, also known as explicit memory, is about personal history, facts, events, knowledge, vocabulary, or way finding. For example, knowing when you were born, knowing what day or month it is, knowing what season it is. When we talk about memory in everyday conversation, we are generally referring to our declarative memory.

Declarative memory is always impaired with dementia, so we need to find ways to provide the missing information in the environment. It's useful to have photo albums clearly labelled with clean, clear, coloured pictures, if possible. Make up some storybook collections about some personal stories now to be able to read back to them in the future, to remind the person of who they are. Procedural memory, also known as implicit memory or muscle memory, is the autonomous habitual or motor skills requiring repetitive muscle movement. Example, riding a bike, driving a car, cleaning your teeth, feeding yourself. It refers to relatively effortless, unconscious, and automatic forms of learning and memory. Muscle memory, or procedural memory, tends to be less damaged in people with dementia.

Our focus is on retained ability. The Montessori approach supports engagement by focusing on what the person can still do, by using procedural memory, and by providing support for damaged areas of declarative memory. Montessori-based activities enable persons with dementia to be engaged with activities of meaning and pleasure using a strength-based approach. It is successful because it is based on the use of muscle memory. As this muscle memory is often maintained throughout the progression of people living with dementia, the activities can be very successfully used as a rehabilitative or restorative measure.

Just to recap, dementia commonly affects declarative memory, language. For example, a person who has English as a second language may revert to their native tongue as their dementia progresses. May lose their insight. Are they hungry? Are they cold? Are they thirsty? Attention, I think we've all experienced people living with dementia whose attention spans may become decreased over time, unless they're actually interested in what they're doing, then we see improvement. And the initiative – what we need to do is be the starter motor for them, to set them up so that, or to begin an activity so that it's ready, and we can just simply demonstrate how to get started, and then they can keep going.

The abilities commonly retained, as I've already said, procedural memory. Engagement through the sensors, the person can often still see, hear, smell, taste. That often stays with them right through the progression of the dementia. Often, the sensors is what we tap into in the later stages. Can they still read and tell the time? Assumptions are often made that a person with dementia can no longer read, when in fact they may not be able to read a 12 font, but they can read something that's 24 font or bigger. Large print books or large print newspapers are a good thing to have. When telling the time, think about what kind of a clock they might have learnt to tell time with when they were younger. A normal round clock and not a digital clock.

Social skills, they can still say hello, still shake hands. They still know or have an understanding of what's required of them. Emotions, remember, at a basic fundamental emotional level, the person living with dementia can still feel what's going on around them. They're still sensitive to how we are when we are working with them, or when we're doing things with them. In knowing the person, we have to gather information regarding their needs and their preferences, and likes and dislikes. Knowing the person as a unique individual helps us to plan the appropriate support strategies to promote engagement. Consider their strengths and abilities to help us plan opportunities that will provide a sense of purpose, enable independence, support success and achievement, and focus less on inability.

As communication is central to our sense of wellbeing, we need to know what the person requires to communicate effectively. Also, check that they've got their glasses on, or their hearing aids in if they use. Knowing what the person requires for a supportive enabling environment, physically, culturally, and spiritually. Activity and purpose are essential for a person living with dementia. Each person has their own preference for how they choose to spend their day. Knowing what is important to them helps us to provide opportunities for them to make choices and decisions. This shows the person that we respect and value them.

It also may be helpful to know past and present interests, things that worry them, things that comfort them, who the people are that are important to them? Three things that make their day, personal achievements, favourite topics for discussion, what their general motivation is, places they may have lived during their lifetime, and their work, their roles, and volunteering. What have they done? Bucket list. If I could, I would. Many people have one of those, but it's also important to know the person's habits, rituals, and routines. For many years, my mother read her newspaper every single morning with a hot cup of tea, and she wasn't happy if she didn't have her newspaper, if it wasn't delivered. A little thing, but it's a big thing.

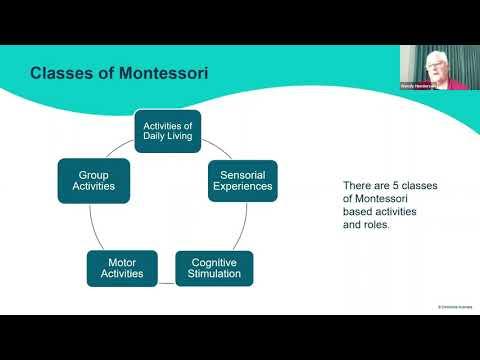

Classes of Montessori – the person's carer or family may contribute valuable information. Montessori puts activities and roles into five different classes or areas. Once you know the person's strengths, needs, and interests, you can design a Montessori program of activities and roles for them. Now, the activities and roles may overlap into more than one class of category. That is fine. The main thing to consider is that the activity or role matches the individual person, their interests and skills. As examples, activity of daily living: dressing, cleaning your teeth, buying groceries, sorting their clothes cupboards, cooking, setting and cleaning a table, washing up, flower arranging, raking the leaves, sweeping, dusting, ironing, laundry, folding clothes and towels, rolling wool, sanding, cleaning shoes, silverware or leather goods.

Sensorial experiences examples, guess the sound or sing a song. What is the taste? What is the scent or smell? What are you feeling? Using different textured materials, feet in sand, petting an animal or a soft toy, a hand massage, a rummage box with sensory items. An example could be a picnic at the beach can incorporate all of these things, or it can be as simple as sitting having a coffee.

Cognitive stimulation: looking at photo albums and sorting your photos into specific topics, shape, picture sorting and matching, matching pictures or items, the sorting activity. Where does the item go? In the kitchen, or the bathroom, or the shed, or the bedroom? Find an item in a magazine, do a jigsaw puzzle, and pairing socks. Motor activities can include treasure hunts, golf ball scoop, pegs scooping, putting pegs onto a container, hitting the balloon, throwing balls or bean bags, walks, using tongs to separate items, walking the dog, dance classes.

Group activities: reading groups, and the hint here is to use large print books, music sessions. There can be so many variations on music sessions, as I'm sure you will understand. Work stations: there might be something where two or three people have got some items to be repaired, and they work together to do that. Reminiscing groups, always good fun. Now, armchair travel takes a very different way these days with the use of iPads, with the iPads on their own, or iPads connected to the TV, to go through photo albums, or to try the various apps available to look at things that are overseas, for example, particularly when we are not able to travel. Montessori encourages the use of both group and individual activities and roles. You are not limited to the lists that I've just given you. Again, it will depend on the person's interests and abilities.

I'd like to talk about the 12 principles of engagement. They're designed to support interaction and engagement when supporting a person living with dementia. When we apply the principles, we are focusing on the person's capabilities, and capturing their interest, and showing respect. People with dementia are often confronted with what they can no longer do, or with the mistakes they make. The principles are designed to focus on what they still can do, and need to be error-free. The principles are structured in the order that you might use them when interacting with a person. A note, these are not just applied to recreational activities and roles, but also to activities of daily living.

Principle number one, give an activity a sense of purpose and capture the person's interest. Number two, invite the person to participate. I often combine the two of these. An example might be, "It's a beautiful day today, I thought we'd go out for coffee, would you like to have a shower and get dressed now so we can go?" There is also including choice in that in number three. Number four, talk less, demonstrate more. We often use the term, watch me, and start to demonstrate something. And then we say to the person, "You try." Use as little vocalisation as possible when demonstrating the activity, to allow your person the opportunity to focus exclusively on the activity or the task.

Physical skills, number five, focus on what the person can do. Number six, match your speed with the person you are caring for, so slow down. Often, we all are used to working and walking way too fast. Number seven, use visual hints, cues, or templates. Popping the towel over your arm to indicate that it's time to get into the shower, as a cue. Give the person something to hold. Go from simple tasks to more complex ones. The activity is structured to be presented at the person's level of skill and ability to promote success, and enhance self-esteem. Number 10, break a task down into steps, make it easier to follow. Number 11, to end, ask, "Did you enjoy doing this?" And, "Would you like to do this again another time?" Number 12, the most important one, there is no right or wrong. Think engagement. I often have people say to me, "I don't know if I'm doing this the right way or not." My response to them is always, "Did your person look happy? Were they responding?" If the answer is yes, then there is no right or wrong. It's about being engaged.

When applying the 12 principles of engagement, remember to invite the person, minimise your talking, and demonstrate instead. Focus on the experience rather than right or wrong, and use the feedback questions to finalise the activity. Something for you to consider – does the physical environment in your home support meaningful engagement? Is it too noisy? Have we turned off the background noise of the TV or the radio? Is there plenty of light? Are the curtains wide open? Is there plenty of light in the room so the person can see what they're doing? Do we have uncluttered space? An example there is to ensure that the dining room table is cleared off so that you haven't got other clutter on the table interfering if you are going to say, do a jigsaw puzzle. Can they find their way? Can they find the bathroom, for example? If your doors are all the same colour as your wall, how do they know which room is the bathroom? What do you have on your door to indicate where the bathroom is? And colour contrast. If the doors and the walls are all the same colour, they may not even know that there is a door there. Same in white bathrooms. They may not know, be able to define where the toilet is apart from the basin.

What changes could you make to support your person's engagement in meaningful activities? As a conclusion, a Montessori approach provides a vehicle for shaping a purposeful, meaningful community in which people with dementia can live. It aims to circumvent disability, create a community where people are enabled, supported to be independent. This begins and ends with choice. Our mantra at Dementia Australia is, “give it a try”. Quality of life is everything.

For further information or resources, go to the Dementia Australia website, on the website on the screen in front of you. There are also this Relate, Motivate, Appreciate, which is available as a pdf. There is a set of videos called “Purposeful Activities for Dementia”. It is a Montessori-based professional development and education resource. Everybody can use these videos, there's some great ideas on them. They're available on the same website. We also have the Centre for Dementia Learning Education programs at dementialearning.org.au. After that, the National Dementia Help line on 1800 100 500. Thank you for attending this webinar.

[Title card: Together we can reshape the impact of dementia]

[Title card: Dementia Australia. 1800 100 500. Dementia.org.au]

[END of recorded material]

Creativity resources

- YouTube channel: Art for Alzheimer’s care

- Explore and inspire: taking creativity into every corner of the home

- Treasury of arts activities for older people

- OPAN Covid-19 Webinar

- Artintuit

- Forward with dementia: art and people living with dementia

- Creative Connections, by Katie Norris and Brush

- Welcome Collection: the Key to Memory

- Australian Music Therapy Association

- Music Attuned Care

- Play Lists for Life

The National Dementia Helpline

Free and confidential, the National Dementia Helpline, 1800 100 500, provides expert information, advice and support, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. No issue too big, no question too small.