Talking to someone with dementia

It’s a basic human need to be able to express yourself and be understood by other people.

But for people with dementia, communication can become harder. They might:

- have trouble finding words, or say a related one instead of the one they mean

- speak fluently but not make sense

- have difficulty expressing their emotions

- find reading and writing harder

- ignore conversations or respond inappropriately

- get frustrated with themselves and the people around them.

If someone you care about who lives with dementia is struggling with their communication, encourage them to seek professional support early. This includes having their hearing and sight checked, and possibly getting support from a speech therapist.

These are some tips and strategies to help you talk and connect with someone with dementia.

Tips for talking

A caring and positive attitude when speaking to a person with dementia can make a big difference. They may not always understand what is being said, but we still show our feelings through our body language, tone and actions.

Here are some ways you can help support your friend or family member when you’re talking with them.

Showing respect and understanding

- Include the person in conversations. Speak directly to them, not just to the people around them.

- Don’t assume what they can or can’t understand.

- Use their name when you’re talking to them.

- Be interested and ask questions.

- Actively listen to what they’re saying. Put down your phone and try to ignore your mental to-do list.

- Provide validation by accepting what they say. For example, if they think their kids are coming home from school, respond to their statement without contradicting them.

Speaking

- Speak calmly and clearly.

- Use short sentences and share one idea at a time.

- Allow time for the person to understand and respond.

- Use names and relationships.

- Draw simple pictures if you’re explaining something.

- Ask simple, direct questions. Try yes/no questions, or offer just a few choices.

Using body language

- Make eye contact. Show you’re listening by nodding and leaning in.

- Express your feelings through gestures and facial expressions.

- Hold their hands to show warmth.

- Smile at them.

Creating the right environment

- Get rid of competing noises like TV and radio.

- Check that they’re paying attention before you start speaking.

- Stay still while you talk.

- Make sure all family members and carers communicate the same way.

Things to avoid

- Avoid arguing with them.

- Avoid asking questions that might alarm them or make them uncomfortable.

- Don't order the person to do something. Make suggestions instead.

- Don't ask for detailed memory responses, or insist on them trying to remember recent events.

Hearing loss and communication

Hearing loss is common in people with dementia, and it can affect how easy it is to communicate.

In this video, Adult Specialist Audiologist Catherine Hart explains how we hear, the warning signs and impacts of hearing loss, how hearing aids and other assistive devices can help, the importance of communication tactics, and how to access hearing services.

Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Hearing and Dementia. Dementia Australia.]

Catherine: Hi, everyone. Thanks for dialling into our webinar today - Hearing and Dementia. I'm Catherine Hart, an audiologist at Hearing Australia. Before we start, Hearing Australia would like to acknowledge and pay respects to the many traditional owners of the lands on which we are meeting today. I pay my respects to Elders past, present, and emerging, and acknowledge the longest continuing culture on earth. I also extend that respect to any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people joining us today.

So, what are we going to cover in this session? We're going to look at hearing loss facts and figures, and how we hear, also hearing tests and audiograms, the warning signs and effects of untreated hearing loss, hearing aids, assistive devices, and how they can help people living with dementia, and in fact, all with a hearing loss, communication tips, and how best to access hearing services.

So, hearing loss facts and figures. Hearing loss is probably a lot more common than you may think, with most Australians to be touched by hearing loss at some point in their lifetimes. One in six of us over 15 years of age has a hearing loss, and this is predicted to rise to one in four by 2050. Hearing loss is more common as we get older, so by 60 years of age, 60% of us will have a hearing loss. 70% of us will by the age of 70 years, and 80% of those 80 years of age. It's also more common in men than women.

Seven in 10 indigenous Australians also have some form of hearing loss, and half of all childhood hearing loss is preventable, as is over a third of adult hearing loss, and that's typically noise-induced type hearing loss. You can also see in the graph here that more than 80% of residents in aged care facilities in Australia also have a hearing loss.

So, how then do we hear? Welcome to the world's most advanced sound system. It's pretty incredible. There are three parts to the ear. There's the outer ear, which is this section here, including the pinner that you're all very familiar with, and the ear canal. We also have the middle ear which is this middle component there, including the eardrum and the ossicles, which are the three smallest bones in the body. We also have the inner ear here which includes the cochlear, which is this snail-shaped structure, and the semicircular canals, which help with balance. Sound is harnessed by the pinner and sent into the canal. This then causes the eardrum and the three little ossicles to vibrate. This sets up travelling waves in the cochlear, which is actually fluid field. There are tiny hair cells in the cochlear that converts sound into electrical impulses that are sent up this auditory nerve to the brain.

Depending on which part of the hearing system is affected, a hearing loss is either a conductive hearing loss, so that's a problem with the sound being conducted through that pathway. For example, wax, perhaps, in the ear canal, or perhaps a middle ear infection in this section here. It can be a sensory neural hearing loss, which is a permanent hearing loss, and that's often an issue with the little hair cells in the cochlear we were just talking about, or it can be mixed, which is a mix, of course, of the two. Perhaps the person might have some wax in their ear canal that's blocking it, and they might also have a noise induced, or an age-related hearing loss affecting the cochlear. Hearing loss can be congenital so people can be born with hearing loss, or it can be acquired. There's a lovely video showing all of that in action, and the link is there at the bottom of the screen.

So, how then do we test hearing? Hearing tests are plotted on an audiogram, and this is a graph of the very softest sounds that a person can hear. On the left-hand side of the graph here, you can see sound in decibels, from very soft at the top to very loud at the bottom. So the further up, the better the hearing. Across the top, we have pitch or frequency. From low pitches, to mid pitches, to very high pitch sounds like S for Sally, F for Fred, for example. Here, you can see an audiogram of everyday sounds. So, a fridge is a low-pitched soft sound, whereas an aeroplane is a loud, high-pitched sound.

And in terms of hearing loss on the right-hand side here, you can see that we have the normal section of the audiogram, moving down to a mild hearing loss which would be affecting communication in a mild way, moderate hearing loss, right down to a profound hearing loss where there isn't much hearing at all there except, perhaps, for very loud sounds or environmental sounds.

So what does a hearing loss sound like? Often, people assume that all sounds are equally affected, but that isn't the case. Some pitches are affected more than others. For example, the low pitches might be perfectly normal, dog barking, vowels of speech, clapping hands, those sorts of sounds the person might be hearing really well, but they might be struggling with some of those higher pitched sounds, such as the consonant sounds. It might be difficult for somebody to hear the difference between 60 with an S for Sally, and 50 with an F for Fred without looking, perhaps, at the person's lips. So, let's have a quick listen now to what a hearing loss might sound like. Here, we have a snip of speech for a normal hearing person, so this snip isn't filtered at all. Let's have a listen.

[Plays audio]

Speaker 2:

The show is a sellout.

Speaker 3:

Well, the weekend is always busy.

Catherine:

Now with a mild hearing loss,

Speaker 2: (slightly muted)

The show is a sellout.

Speaker 3: (slightly muted)

Well, the weekend is always busy

Speaker 1:

And now, a severe hearing loss, so moving down that audiogram we were just looking at.

Speaker 2: (very muted)

The show is a sellout.

Speaker 3: (very muted)

Well, the weekend is always busy.

Speaker 1:

Catherine: As you can see, it's not just losing volume, it's really losing clarity as well as we move down that range, so it can be really difficult. And instead of he hears when he wants to, it's often more a case of he hears when he can.

So, what are the warning signs and effects of hearing loss? Either yourself or a loved one may be asking for repeats a bit more often, they might need the radio and the TV turned up louder, and they may have lots of difficulties when it's noisy as well. They may struggle to hear on the phone, and/or even to hear the phone ring. They might not respond when their back's turned and the sounds going the wrong way, for example. Sometimes, there might be dizziness, or ear pain, or ringing, buzzing, pulsing, pounding noises in the ear called tinnitus, and sometimes, that can also be a warning sign of hearing loss. And, of course, those sorts of symptoms would be best checked with the GP too before you have your hearing check.

Unfortunately, often, people with hearing loss start to withdraw from social activities. They tend to really become a bit isolated at times, because it's quite exhausting having to fill the gaps as you're talking, and they really do miss out on quite a bit of speech and communication. If there's a difference between the ears, the person might also have trouble localising or telling the direction that a sound is coming from as well, so that can be a warning sign for those people.

Untreated hearing loss can have psychological, emotional, social and physical impacts, not just on the person with hearing loss, but also their family, friends, carers, and so on. We've talked a little bit about listening effort and fatigue – it can be frustrating as well, and stressful, and sometimes, can cause the person with hearing loss and their loved ones to feel depressed. We've talked a little bit about social withdrawal and isolation, and it can also be a real safety risk if that person's not able to hear the phone ring, for example, or hear traffic on a busy street, or a smoke alarm.

Untreated hearing loss in middle life is also associated with increased risk for dementia of course, as well. It can also cause reduced opportunities in the workplace if the person's communication is affected, and reduced quality of life, especially if it's a significant hearing loss, and/or the person has other disabilities in addition to hearing loss. For example, they might have a vision impairment, and that makes it really hard, then, for them to access visual cues, and that can be really difficult, and presents some unique challenges.

The good news, of course, is that hearing aids and assistive devices can help. Hearing devices help to improve the social, the emotional, the physical, and the psychological wellbeing of all people with hearing loss, including those living with dementia with a hearing loss. They also allow people living with dementia to stay connected and included, which is incredibly important, of course, too. There are different styles and levels of technology to suit people with all sorts of different hearing needs.

Hearing aids are individually set to the audiogram we just looked at, and they really help to keep those hearing pathways active. There are also other devices called assistive listening devices. Often, things like headphones, and those sorts of things that we'll talk about shortly, and they can also help. Hearing aids of course, do take a little time to get used to for new users, of course, and we'll talk about that a little bit more shortly.

Hearing aids have come a long way and are really very useful, and have some great benefits, but they are an aid, not a cure. They're a microphone, in effect – they still work best in quiet, and within one and a half metres of the person that you're talking to, or the sound you're listening to. Hearing aids can only safely give back half of the hearing that's been lost. If we were to give any more than that back, we would risk damaging the hearing that remains.

Modern devices are digital, they work harder in noise, and many are automatic. We talked about different styles and features. There are some rechargeable options. You can see here on the right-hand side, we have some ITE, or some in the ear type hearing aids, some behind the ear hearing aids. There's a variety of hearing aids, some are stronger than others, and they're available to suit people with various hearing and communication needs.

Hearing aid decision aids can be really useful for family and people as they're trying to decide which sort of hearing device might be best for them, but we touched on how tricky it can be to get used to hearing aids as a new user, and it's important that family, and friends, and carers are available to really support and help the person persevere. Some hearing aids have other features like Bluetooth streaming, which can be really useful, particularly for streaming telephone, or TV, or music directly to the person's hearing aids. And we know music is a great way for people to remain connected and to reminisce, and that can be really useful as well.

There are also other devices such as remote microphones, and you can see this man in the picture here on the right-hand side is wearing what we call a neck loop system, and that talks to a microphone on the table. The neck loop system can be worn by itself, or it can be used with hearing aids as well. Remote microphones really help reduce the effects of distance from the speaker, background noise in the room, and a really echoey, reverberate sort of environment. And some offer other features too, we've talked about Bluetooth, but Telecoil can be very useful as well.

There are other listening devices out there, of course, as well, including television devices where the person pops the little headset on and listens to the TV without any background noise. Personal amplifiers – instead of wearing a hearing aid, the person pops the headphones on, and this turns all sounds up, and that can be really useful for some people as well. Amplified telephones with large buttons, and smoke alarms for people with hearing loss - so very loud smoke alarms so people can hear them, amplified doorbells, that sort of thing.

Sometimes, hearing aids aren't enough. We know that hearing aids only give half back of the hearing that's been lost, so for people with a fairly significant hearing loss, hearing aids might not be enough. You may have heard of the cochlear implant, and that's a surgically implanted option for people who obtain little or perhaps no benefit from hearing aids, and that can also be suitable, sometimes, for people living with dementia. There are also some implantable bone conduction devices available too.

So now, we've talked a little bit about the hearing devices and all the options that are out there, let's look more at communication tips, and I think we can all be better communicators. We know hearing aids are an aid, not a cure, and can never be the full answer, because they're only giving half back of the hearing that's been lost. So, what else can we do to really help communicate with people with hearing loss?

The first thing, of course, is to face the person directly, be at the same eye level, and that, again, really helps with the lip reading. Also important not to shout, just speak normally – hearing aids tend to distort if you're shouting, so that's something to avoid. Obviously, keep your hands away from your face. That really helps as well with the lip-reading component, reducing background noise, turning off the TV or radio, if you have the choice of two rooms, one cozy, and carpeted, and cushions, and upholstered chairs, always choose that over a hard floor room, or a large auditorium room, or hard chairs, that sort of thing. Cozy is best.

Make sure the light isn't shining in the person's eyes, because that can make things very hard for lip reading, of course, as well. And it's important that if you're not being understood, always try to find a different way of saying the same thing. We know that not all sounds are equally affected, and often, consonants are more affected than vowels for some people. So again, it's just about making sure that you are understood, and be ready to rephrase as needed, of course, as well. And be patient – the person might have trouble understanding speech even with the hearing aids in.

Other communication tips that can be useful when communicating with people living with dementia. Of course, calm and friendly approach and taking it slow. Keeping sentences short and simple if needed is important, particularly if the person is tired, it might be the end of the day, and these sorts of tips really help when communicating with anybody. Removing distractions is important as we've said, and really allowing time for the person to respond. Showing and telling with actions and gestures can be really useful as well. For example, if you're showing your loved one, how to change the hearing aid battery, instead of just using words you could show, demonstrate as you go, that can be really helpful. And as always, be flexible and positive, and check that the person has understood.

We've talked a lot about hearing aids working best within 1.5 metres of the speaker, and of course, that's been a real challenge more recently with social distancing and mask wearing. Here, hearing tactics and strategies become even more important. Speech sounds are softer, further away, and background noise is also more intrusive because the speech has to really compete with the other sounds going on in the environment. When you're at a distance, it's also harder for the person to lean in, or try and access visual cues and see the lips as easily. And often, then, the person you're talking to has to increase their vocal effort, they have to speak louder, and that can be really hard as well. And the last thing we want is for them to say, “You know what? Don't worry about it.” That would not be good at all either.

There's some great speech to text apps out there such as NALScribe, and they can really help by converting speech to text on an iPad, for example, or on a smartphone, and it's easy, then, for people to follow that in real time, and they're available in a number of different languages as well. Speech to text apps can be really useful also when people are wearing masks, because masks really muffle those high pictures.

So, how best to go about accessing hearing services and having your hearing checked, or the hearing of a loved one checked? Hearing Australia was established in 1947 for the World War II vets, and also, at the same time, there was the rubella outbreak and lots of deaf babies were born. Hearing Australia is a Commonwealth Statutory Authority, and we're part of the Department of Government Services. We have over 180 permanent hearing centres, and more than 600 visiting sites and outreach locations in various communities around Australia.

We offer home visits and telehealth services too, if that's appropriate. We also offer aged-care education programs. We have our own research arm, which is the National Acoustic Laboratories, and you can see our website there. Hearing Australia is the sole provider of specialist hearing services, to hearing impaired children under 26 years of age, eligible adults with complex hearing and communication needs, and many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients, seen under the Commonwealth Government's Hearing Services program.

People can contact either a Hearing Australia or their local hearing provider to arrange a hearing check. It's really important that hearing is checked as often as vision. Subsidised hearing services are available under many programs such as the Commonwealth Hearing Services Program. It's always important that people see their GP first to rule out any medical causes of hearing loss, for example, wax, ear infection, those sorts of things.

Ways to connect

Communication goes beyond words and talking. It’s also an important way that we connect with each other. If your friend or family member is finding it difficult to talk to you, these are some ways you can maintain your connection.

Reminiscing

Reflecting on past events can be rewarding. Even if your friend or family member can’t actively talk about the experience, reminiscing together can bring you both joy. However, always be sensitive to their reactions. If something upsets them, stop and do something else.

Music

Music can be a great tool when words fail. Familiar songs can bring up memories and emotions. You could try playing music, singing or dancing together, or going to music concerts. For more on music, see our page Activities for people with dementia.

Making a memory book

Creating a memory book together is a wonderful activity. This visual diary captures the person’s life milestones. Here’s what to do:

- Use a large photo album or a make digital version.

- Keep it simple, with one topic and two or three images per page.

- Use photos and add captions to prompt their memory. You could also include letters, certificates and drawings.

- Include details about their family and friends, pets, their childhood, past holidays, places they lived, their job, hobbies, favourite music and special events.

Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Dementia Australia]

[Title card: Communication problems in dementia – Should I see a Speech Pathologist?]

Professor Ballard: Hello. Today, we're talking about speech language therapy support for people with dementia and their families. First of all, I would like to acknowledge that much of the content for this lecture is based on a co-authored chapter by my two PhD students, Sarah El-Wahsh and Penelope Monroe, and a colleague, associate professor, Fiona Kumfor, at the University of Sydney.

First of all, an overview of the talk. Communication can be affected across the spectrum of dementias, and today, I'll go through components of communication. What is communication? How it interacts with memory? The types and stages of dementia and communication problems that you will see, and the impact of those problems. Also, speech therapy approaches, just a sample, and how they might help, and how you might connect to a speech pathologist.

So, the components of communication. When we want to express our thoughts, our ideas, and communicate with an individual, we go through a set sequence of steps. I will walk you through those now. For example, just say that you noticed this morning that your dog was being chased by the neighbourhood cat, and you want to relay that story to a friend. First of all, you have to retrieve what we call semantics, which are the meanings of words. So, you have a concept for cute, fluffy, says meow, and you have a concept for barks, runs, likes to play with a ball. They're your meanings of concepts. Then you have to generate the sentences to express those concepts to your friend. Are you going to say the cat chase the dog? Or do you want to focus on the dog and say the dog was chased by the cat? Then, you need to retrieve the sounds of those words, K-A-T. And then, finally, all of that comes together to produce movements. We have to generate commands that drive our mouth, our tongue, our lips, to produce those words in that sequence of sentences or words, to produce the sound that our listener will hear and interpret.

This process happens this way when we go to say what we want to say, but also, we're trying to understand what others say to us. So, we hear their articulation, and then we have to match that with our sounds, process their sentences, and extract the meaning of what they're saying to us, so it's both production and comprehension, and memory interacts with this critically all through these processes. So in terms of meanings, we have something called explicit memory, which is memory that we can think about and reflect upon, and it's autobiographical memory for events, what you did, when you saw the dog being chased by the cat, but also other events in your life through your whole life. Facts, things that you know – you know that volcanoes put out lava, but also the words. The mapping of those sounds, K-A-T, to the meaning, fluffy, cute thing that says meow.

Also, sentences. So, we use our memory in terms of remembering the story that we want to tell, and what is the best kind of sentence to express that story. Do we want to focus on the cat or the dog? Are we going to say the cat chase the dog, or the dog was chased by the cat? And so, really about the roles of the characters within our sentence. The sounds, when we are producing these sounds, we have to remember the sounds that match up to the word, but we also have to hold those sounds in memory, and we also have to hold the bits of the sentence in memory so that we can start to unfold the meaning, and make sure our story is making sense. When it comes to movements, though, these are implicit memory. So it's a different kind of memory, and it's a memory that's really automatic. It's what underlies our habits, things that we do automatically, reflexively, without thinking. And speeches that, the movements of speech are automatic routines, and that allows our speech to be extremely fast and fluent.

In terms of dementia, we know that dementia is an umbrella term under which many neurological conditions fall, and the symptoms vary greatly between these types. Most research attention has been given to communication problems in Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia types. And these are often associated with a particular communication problem called primary progressive aphasia, but they can also just be associated with general communication problems that aren't classified as primary progressive aphasia. So, we're going to focus on those two types, just because that's where most of the work has been done. There has been a lot of work on Parkinson's disease, but much more in terms of speech movement control, not so much on the impact that dementia can have in some individuals.

Many of the speech therapy assessments, and treatments, and services that have been developed for these types are also used in the other dementia types. So, even though I'm talking about those two types particularly, you can expand this out to other types. The communication changes in dementia can occur across all the different components of that communication system I showed you. And initially, the specific communication changes a person with dementia presents with are influenced by their type, the type that they have, because the location of the neuropathology in the brain is usually quite focused early on. However, as a disease progresses, they begin to look a lot more similar.

In the early stage, word finding difficulty is extremely common. It's the most common complaint, alongside memory problems, across the dementia types. So, what you see or experience may be trouble with words, word-finding. So, this is talking around the word, instead of saying “scissors”, you say, “The thing for cutting”. You use vague words like “thing”. Semantic errors, these are errors where you select the wrong words. You try to get the word orange, but apple comes into your head, or you make sound errors. So, you're going for “apple”, but it comes out as “apfle”, which is not a real word. So those things are the most common types of behaviours that you see. Also, you may experience, or a person may experience, formation of sentences changing. So, using shorter, simpler sentences, or sentences that have grammar mistakes, so saying, "John said she was sick," instead of, "John said he was sick", and the person may notice it and try and fix it, or they may not notice it.

Understanding is also an area that can be affected. This can be because the person loses the link between how a word sounds and its meaning, or they may have trouble decoding and hauling it in their memory, so they can't process complex sentences and remember, “Was it the cat doing the chasing or the dog?” So, those two things. They might say things like, "Scissors, oh, what's that?" Or just not be able to interpret those complex sentences. Social language is another thing, and that's something that there is less research in, but it's just as important. And here, you can see people may have trouble keeping a topic of conversation going. They might be flipping around, they may have trouble sharing equally in a conversation, and that could be talking too much, or not enough. Or not interpreting plays on words, so understanding that words can have more than one meaning, and so, missing the humour and sarcasm that we use all of the time in our conversation.

I'm going to jump out and show you a couple of examples of trouble with meanings, trouble with sounds, and trouble with sentences and movement. And these are beautiful videos made available from a group in Britain.

[Plays video 1]

Speaker 1: Your hair stays nice.

Speaker 2: Oh, buddy, it's all right. Oh, my Lord. I thought, "Bang, bang, bang, bang." And I thought, "Oh my God. Oh my." And I thought, "I'll be darned. It's all right."

Speaker 1: Who fixes it for you?

Speaker 2: Dee.

Speaker 1: Dee.

Speaker 2: Who is she?

Speaker 1: Oh, oh, oh, Millie.

Speaker 2: And I saw such-and-such.

Speaker 1: Who's Millie?

Speaker 2: Millie.

Speaker 1: Who's Millie?

Speaker 2: Millie.

Speaker 1: I don't know Millie.

Speaker 2: Oh, no, no, she's gone. She's gone like that.

[End of video 1]

Kirrie: Okay, so that's an example of someone having difficulty with meanings. They're using a lot of vague words. You get what she's talking about, but she's not using very specific words, and doesn't understand the question she's asked. Here is one that is an example of difficulty with sounds, and this person has quite a bit of insight.

[Plays video 2]

Speaker 3: So now, I am actually, am a priest. I'm not actually the vicar, because I don't get paid. I'm not in charge of the parish, but I can take the services. I can't read very well. So, I don't, I haven’t seen a book for about three years. I can't read a book. I can say the words, sometimes, and sometimes I can't. And in a sentence, I can't make it make sense. If even I can say each word, I can't make them say what it's supposed to say. It's just like "Da, da, da, da, da." It doesn’t come, not as if, it doesn't mean anything. And I can't remember just everyday words. It's not like when you can't remember somebody's name. It's not like that. It's just a word like table or the window, or things you've said for all your life, and suddenly you can't, and then one day scalf-, there's one word I can never remember, called (indecipherable). Actually, I can't even say it, and I know what it is. When they're in a building, they have the [indecipherable], whatever it is.

[End of video 2]

Kirrie: Scaffolding is the word she's looking for. And one more example, which is showing difficulty with sentences that are a lot shorter, and speech is a lot slower and less fluent.

[Plays video 3]

Speaker 4: It affects the telephone most, and I used to wave my hands about, and facial expressions, I can't do anything like that on the phone.

[End of video 3]

Kirrie: Okay, so that last one, which was more about complex sentences and movement is less common in Alzheimer's type dementia, where typically, it's more about sounds and comprehension, having trouble with reading, but also, possibly these vague words and reduced understanding. So, in the middle stages of progression in these conditions, the person may experience increasing difficulties with their communication changes, and this will obviously lead to greater limitations in everyday activities. For example, both speaking and understanding might become more difficult, and the person with dementia may begin to speak less. And then in the later stage of the disease, understanding of language and verbal output may become very limited, with significant difficulty making needs, and wants, and thoughts, and feelings known, and really having to communicate through other modalities, being quite passive and not having rich interactions.

And obviously, these changes can be overwhelming for both the person with dementia, and the people around them, their loved ones, their carers. And this can impact, both, the person with dementia, and those people around them in terms of loss of friendships, changing in relationships, loss of intimacy, reduced quality of life, depression, and social isolation, and loneliness. And it's very important to be thinking of these and trying to manage these, both for the person with the dementia, and for the carers.

A speech pathologist is a vital part of the multidisciplinary team in dementia care, as they're experts in assessment, management of communication. And as we've just seen, communication impairments can occur across the whole period of the disease, and have a significant impact on multiple people. So, at present, referral to speech pathology for communication changes in dementia is remarkably uncommon in Australia. However, a speech pathologist can and should be involved at every point of the journey, even if they're not showing sentence problems or meaning problems, the interaction component can be critically important, and we can help with that. And so, there is no single gold standard assessment to assess communication and dementia. There are lots of different assessments out there that can be used. We do a comprehensive battery of assessments, and we try to cover all stages of the World Health Organisation's International Classification of Functioning, disability, and health, called the ICF.

So, I've talked very much about changes or impairments in body functions and structures, so the actual problems in sentences and meaning and so on, but we also evaluate how that impacts on the ability of a person to do the activities in their daily life, whether it be talking with their grandkids, or their spouse, or still being at work, and how that affects whether they can participate socially and in their workplace. We also look at environmental and personal factors – so is the person living at home or in a residential facility? Do they have a really strong support network around them or not? And personal factors, how motivated are they? What is their memory like? What is their insight like? Those sorts of things, whether they have other medical conditions going on as well.

We can help in quite a lot of areas that are all associated with communication. So here is a summary: speaking, finding words, making your verbal output more organised and efficient, listening, understanding what others say, reading and writing skills, social communication skills, all about the interaction, communication aids, when you need some other method to support your speaking or listening. So, whether you need to be learning some gestures, or whether there are some apps you can put on your phone to help with your communication, whether you need some picture books to support getting a conversation going and helping your listener understand what you're saying.

Critically, we do a lot of work in partner training. Partners, often, an interaction between a person with dementia and their primary carer, their spouse or whoever, the communication can be quite dysfunctional because the carer doesn't know how to deal with these communication changes, and we can help make that easier. Also, speech pathologists are the key people who are involved in swallowing difficulties, which sounds a little bit different to all of these other things, but we are the experts in helping individuals with the movement process of eating, chewing, managing liquids, making sure you don't choke or have fluids falling into your airway. And so, if there are any swallowing problems, usually later on, then we get involved to make sure everything is safe, and working with nutritionist and so on, to make sure nutrition is maintained whilst safety is critically ensured.

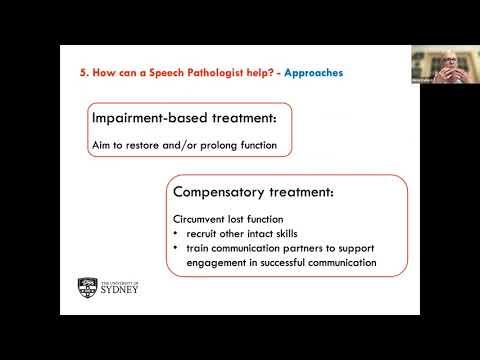

As a speech pathologist, we have two primary approaches and these map onto that ICF framework in terms of impairments, activities, and participation. We have impairment-based treatments, particularly, we use these in the early and possibly middle stages, where we actually go in and look at what are the communication skills that are affected. And we work on those communication skills, and we know that we can actually improve them, even though this is a progressive condition, people often start to compensate for these difficulties, but not in very effective ways. So, we can come back in and help them build some skills back up again. And, of course, it is a progressive condition. So, what we are doing here is just trying to prolong, as long as possible, prolong communication function, because ultimately, people want to speak, they want to still be able to communicate through speaking. So, we are trying to prolong that function as long as possible, and sometimes, this can actually help someone stay at work a little bit longer. It's not uncommon that people say communication problems are a major factor in deciding to leave work early.

Compensatory treatments are our other approach, and that is trying to circumvent the lost communication function, or the impaired communication function. So, we are looking at what other intact skills are there that a person can bring to make their communication more effective. And also, this is critically where we bring in the communication partners and do this partner training. So, we are trying to help partners support the individual to be more engaged in communication and social interaction, because we know that's at the heart of quality of life and wellbeing. To give you an example of a couple of these interventions, speaking and finding words, we call these word retrieval therapies, and we're typically in the early and middle stages, where we work with an individual and their family to find the personally relevant vocabulary they need to work on. We have a number of techniques giving the first sound, identifying features of the word, practising retrieval through gradually giving them the word to imitate, and then having them gradually take longer and longer to imitate that word so that, finally, they're doing it by themselves. And also, what we call errorless learning, which is, well, we do ongoing high intensity practise, but errorless learning is used, which is making sure that they're getting really, really high success rates. And so, that ongoing high practise of these different techniques can really help. And research evidence shows us that practise in meaningful activities really makes the effects stronger, last longer, and also, people with stronger motivation, memory, insight, and better support networks typically get a greater benefit.

Another area is working on organised and efficient output, and this is usually what we call narratives and scripts. So, when we go out to coffee, we tell stories to our friends about things that have happened. And so, they're narrative. And scripts are things like you might be wanting to give a speech at your daughter's wedding that's coming up, so a script is essentially a script that you're going to practise, practise, practise, so that you can tell that script at the wedding. So, one is much more free, and the other is a really wrote/learnt script. So, we co-develop these important narratives and scripts that are for real life activities. They, again, involve really consistent intensive practice, and they work on all of those things – meanings of words, sentences, understanding, but also social interaction, and making sure your story makes sense. We have techniques such as imitating, reading together simultaneously, and then independent recital, which really help people solidify their production, and there are apps to support this as well now.

What we find with research is that these narrative and script approaches improve the fluency of people's speech, and also, they produce fewer repetitions, revisions, and hesitations as they're going through, because the words are coming more easily. Another strategy that's used a lot, not just by speech pathologists, but is development of memory and picture books. And here, it's really a focus on how you can use these to support communications. So these, again, early and middle stages, collection of labelled memorabilia to stimulate and maintain conversations. And again, it's co-constructed with the clinician, and the person with dementia and their carers, and it's highly personalised for that individual. We often take those narratives and scripts and put them to pictures, put them into the memory book, and then, the person can use the memory book to support them telling that story when they go out to coffee with their friends, for example.

Again, research has shown us that memory books facilitate improved content in people's language, the amount of time they talk, and the frequency with which they talk, improves their meaningful social interaction, their closeness with carers, and reduces frustration, confusion, depression, aggression, and the anxiety related to memory and communication problems. And finally, I'll talk about communication partner training, which tends to be done later in the middle and later stages. It's delivered in pairs, so a person with dementia and their carer, or in groups, and it can be a spouse, or a grown child, or grandchild, or it could be a health professional in a residential facility. And it's delivered by a speech pathologist, and often, also a psychologist. And it works on developing the partner's skills and strategies for improving communication.

It includes education on what causes these problems, what do they look like, what's happening, how they affect communication and make it breakdown, as well as how this is going to change over time. And also, it involves teaching the communication partners meaningful skills, for example, language-based skills like reducing your sentence length, and the complexity of your sentences, and the complexity of the words that you use. And working together in conversations to help the person with dementia elaborate what they're saying and contribute more. Also, non-language-based communication skills like the tone of the voice that you use, the time you give the person to give their response so you're not rushing, tolerating silence, so that a person has time to formulate their response, making sure there's good eye contact, maybe gesturing, and really being positive and encouraging, and also, making environmental modifications, so making sure that when you are going to have these conversational interactions that you minimise distractions. Choose a good time of day when the person is much fresher and receptive, and so on.

These sorts of things, these are systematic treatment programs that people have developed. So, connecting with speech pathology. In summary, communication changes can occur from early in the dementia journey, and will become more prominent as time goes on. And these changes have a significant impact. Communication is what makes us human, it's how we engage with the world. And so, it has a significant impact on both the person with dementia, and the people around them. And speech pathologists can, and really should, be involved at every stage of this process because we can assess, diagnose, treat, and manage these communication symptoms. And we have several evidence-based interventions that can be used at different points of the dementia journey to improve the quality and effectiveness of communication.

How do you find us? That's the challenge. So here are four options. You can tell, don't ask, tell your GP or your neurologist if you want to speak with a speech pathologist, and you may just want to speak with them to say, "Look, this is happening, is that okay? Or is there something we could do?" So, it could just be a consult to get advice, but speech pathologist is the best person to give you that advice in terms of communication. The other option is you can go straight to the National Association's website, Speech Pathology Australia, and the link is here, and you click on resources for the public, and find a speech pathologist, and it brings up this window here where you can enter your postcode, the distance you want to travel, or whether you want a mobile service that comes to your house, your age, your condition. Here, dementia, and it will show you all the speech pathologists who are registered in that area that work in the field of dementia. Unfortunately, most people working in dementia are private speech pathologists, which is quite expensive.

There's another site as well, Karista, that you can do the same thing and it will show you a smaller set of practises in your area. There are also university speech pathology clinics that, not all of them, but some of them do have clinics for working with individuals and families dealing with dementia. For example, at the University of Sydney, we have a clinic that works specifically with people who have primary progressive aphasia that results from Alzheimer's dementia or frontotemporal dementia. So, you can contact universities as well, the speech pathology clinic. Finally, do you need a referral? Well, actually no, you don't need a referral to see a speech pathologist. You can just call them up.

However, the last point here is you'll need to visit a GP if you need to be assessed for eligibility for Medicare rebates through the Chronic Disease management program, if you're eligible. It is expensive to have private speech therapy if you're paying out of your pocket. Public services through hospital outpatients are free, but they're very difficult to get into because hospital speech pathologists have to prioritise in-patients. Services through the university clinic are often free, or at least a reduced cost, so I will end there, and thank you for listening.

[Title card: Together we can reshape the impact of dementia]

[Title card: Dementia Australia. 1800 100 500. Dementia.org.au]

[END of recorded material]

It’s okay to take care of your own health and happiness. If you're struggling as someone who cares for a person with dementia, contact the free, confidential National Dementia Helpline on 1800 100 500, any time of the day or night, for information, advice and support.

The National Dementia Helpline

Free and confidential, the National Dementia Helpline, 1800 100 500, provides expert information, advice and support, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. No issue too big, no question too small.