Transcript

[Beginning of recorded material]

[Title card: Dementia Australia]

[Title card: Addressing the challenges of driving cessation for people living with dementia]

Dr Scott: Hello, my name is Theresa Scott. I'm a senior lecturer and researcher in the School of Psychology at the University of Queensland, and it's my pleasure to speak to you today about addressing the challenges of driving cessation for people living with dementia. To begin, I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which the University of Queensland are situated, and to pay my respects to their ancestors and their descendants, who continue cultural and spiritual connections to country. And just a little bit of background about me, I have been leading a team of researchers with some funding support from the NHMRC, and investigating living with a dementia and driving, from the perspectives of persons living with dementia, their support persons and family members, and the health professionals that support them. And additionally, I have some lived experience in this area. My father was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, and has had to stop driving since.

The key topics that I'll cover in my talk are the meaning of driving, readiness for change, finding a balance, safety and independence, your legal responsibilities as a person living with dementia who is driving, medical assessment of driving and what that might look like, preparing for change, and adjusting.

To begin, I want to talk about the importance of community mobility to wellbeing and quality of life for people living with dementia. So, community mobility is that connection that we have to our local communities, the ability to get out and about and to participate socially. And we know that this is linked with someone who is living with dementia's ability to remain living in their own homes, and in the community, for as long as possible. And driving is the principal mode of transportation to connect to our communities, and it's a common way to stay independent, but driving represents more than just transportation, it represents freedom and a sense of control, so that ability to go where you want to go and when you want to get there. It also represents identity and role for people, so that identity may be involved in the fact that someone sees themselves as the main driver in the household, or a contributing driver to the family or their friends or a volunteer, or perhaps, they've been a professional driver all of their lives. People may become attached to the driving role or attached to their vehicles, and driving is a pleasurable activity for a lot of people – so telling someone to stop driving, it has serious implications if they are not supported through that process.

People tell me through my research that giving up driving can be a deeply personal and emotional experience. Some people may cope very well, but others may be challenged. It can be experienced as a series of losses, it can be a behaviour change, so it’s something that we need to practise, and it can be a significant life event, but we can support people, and we can work with people's strengths to help them through the process of giving up driving. And so, some of the strategies, or some of the things that you might do, in getting ready for the changes if you're someone living with dementia, is you might talk about what driving means to you, and what loss of driving would mean to you, so keep that conversation open and from early on. You might plan early for retirement from driving.

We talk about maybe modifying driving habits, so while you are still driving, maybe you might choose to drive for less, or you might choose to use an alternative form of transport to get to where you want to go while you are still driving, so gradually reducing the amount of driving that you do and relying on other transportation, for example. A gradual shift in the main driver. So, if there is another driver in the household, maybe letting that driver take over some of the driving that you might have otherwise done. You could arrange for home deliveries, for example, on your groceries.

Again, while you're still driving, what are these things going to feel like? That's all about that practising for driving cessation. And you're trying out some alternative transports, again, while you're still driving. So, maybe public transport is a good option for you if it's available in your local area, or if it's something that you think is suitable for you. Taxis, and you might be able to get subsidy vouchers available, and you can talk to your GP about that, perhaps. Or walking might be one option, it's not for everybody, but some people do tell us that they've decided that they may do more walking and less driving if they can. And share riding might be an option, so things like Uber, Ola, DiDi and the like, or you may ask family and friends if they can step in and do some of the driving for you.

And in terms of that adaptation process, what I've found in my research is that there are some phases that people go through. These aren't linear, so that is to say that people may not move through each of these phases sequentially. And in addition, some people may get stuck in one of these phases, and people may need more support in one phase than in another. So, for example, coming to terms might be where you, as a person living with dementia, who is knowing that you have to stop at some stage, coming to terms might be having that effortful thinking process about what it might feel like to stop driving. So it can be personal, or rather, it can be human nature to just avoid thinking about difficult things, but we do know from talking to people who have been through the process that if you do think about it, and you do think about what that might look like, how that might feel for you, that that will set you on the path for helping you transition through that period, through that process.

And then, of course, making the decision that's knowing when to stop, and that might involve you talking to key people, to people that you trust, about helping you make that decision, talking to maybe your GP about that and what driving assessment might look like, and then owning the decision. So, you've made the decision to stop driving, but this is where you need to feel comfortable with that decision, and it's about feeling as if you were part of that decision of course, but feeling like you had some control over it. So again, it's talking to people, talking to people through that process. And the adjustment period or adjusting, this is where you'll still need practical support, but you'll still need that emotional support as well, and so, the people around you will need to have that understanding that while you are getting that practical support, you might still need that emotional support as well.

If we think about finding a balance, so balancing someone's independence and their safety, we also talk to people about at what point might driving become unsafe? And talking to people who, again, have been through this process, what were some of the signs you think that indicated to you that, perhaps, it was time to start thinking about stopping driving?

And first of all, though, I wanted to mention that while driving may seem automatic, we do know that it is a complex task and it does require the function – so the cognitive, sensory and physical functions that are affected by dementia. So these are your visual, spatial skills, your situational awareness, your judgement and reaction time, and of course, your way-finding, but a diagnosis of dementia should never, by itself, be the reason for loss of driving privileges. So, someone should not have their driver's licence taken from them immediately, but because we know that the condition will progress, it means that, eventually, a person living with dementia will have to retire from driving. And we do know that the risks of accidents increase as that condition progresses, and perhaps, sometimes, people may become less aware of their own safe driving.

So, safe driving involves people's reflexes, their spatial abilities, their executive function, so their working memory, and their flexible thinking, and self-control, and their insight. Finding their way around, remembering which way to turn, judging the distance from other cars and objects on the road, so being able to judge where you are within the lines on the road, and judging the speed of other cars, your reaction time, moving your eyes and hands together, and reading and being receptive to road signs. So, as mentioned in that previous slide, it is quite a complex task.

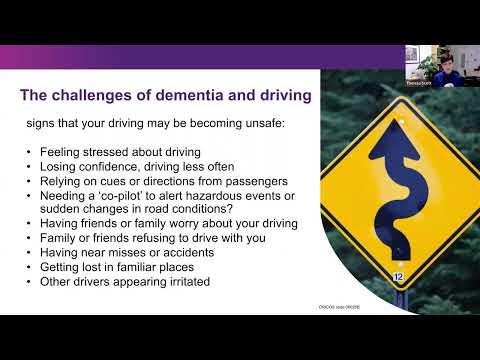

And so, these are some of the signs that your driving may be becoming unsafe, and so, these are what we've learnt from talking to people who are living with a dementia, or supporting someone who is living with a dementia. So these signs may include that, perhaps, you're feeling a little bit stressed about your driving, or if you are losing confidence, maybe you are driving less often. You might be relying heavily on the cues or directions from the passengers in your car. Similarly, you might need a co-pilot to alert you to hazardous events or any sudden changes in the road conditions. Having friends or family worry about your driving, or do friends or family refuse to drive with you. You might have near misses or accidents that show on your car. You might be getting lost in familiar places, or other drivers might appear irritated around you. But it's important to remember here, though, that a single occurrence does not signal that your driving should stop, but it is when these sorts of things are happening more regularly and together, that you might want to start that conversation with your GP, or with those key people around you.

If you are a family member and you are supporting someone who is living with a dementia, who is going through the process of driving cessation, then balancing independence and safety, maybe that period involves raising awareness about driving safety with the person, so talking to the person that you care about, about what safe driving looks like, and that impact of the dementia on their safe driving. So, you might be monitoring their safe driving as well, but consider how and when to raise concerns, and to choose the right person to have the discussion. So, perhaps if things are becoming more difficult for you to raise that topic, then perhaps there's someone else that you might identify that might be better to have that conversation, but the important thing as well here is to choose the timing, to remain respectful, and to keep that communication open.

In terms of your legal responsibilities as someone who is living with a medical condition that is affecting your driving safety, anyone that has a medical condition affecting their driving safety, they must advise their local transport and licencing authority of that – so this is something that we find most people have no awareness of, but you must advise your local transport and licencing authority. It's not necessarily up to the person that diagnoses your dementia, so your GP, for example, you must do that. And that licencing authority will then ask you to take a medical fitness to drive assessment with your health professional, so your GP. And if you do fail to notify, it does have serious implications, and we raise this with people because it is really important to have that understanding and awareness that, once you are diagnosed and you don't notify, then if you are involved in an accident, then you may be considered culpable for the damage, you may lose your insurance, you may be charged with an offence, and you also may get, in most states, there are fines involved as well for not notifying. And in Queensland, we have Jet's Law, and so there are quite significant hefty fines involved with that.

So, you then need to carry a medical certificate to drive If you are over a certain age. In Queensland, it's over 75 years. That differs from state to state, though, or you have that medical condition. And so, again, what we say, along with the ANZ Society for Geriatric Medicine position statement, is that people with a mild dementia may be still safe to drive, and that it's not reasonable to suspend someone's licence based solely on that diagnosis of mild dementia. So they say that a driving co-pilot is not recognised safe practise, so that's, I think, important to remember, and an occupational therapy on-road driving assessment is accepted as a gold standard assessment, and I'll talk about that in a moment and what that looks like for people. And they recommend that regular review, at least six monthly, so being reassessed – so if you are given a medical certificate to continue to drive, you're likely going to be told that you must go back and be reassessed with your GP every six months, but sometimes, that might be sooner.

In terms of what a medical assessment might look like, these are conducted by a health professional, and it's usually your GP. Your GP may give you an off-road test, and that might involve a memory test or a test of cognition, a test of your visual acuity, of your physicality, for example, or an on-road assessment. You might be sent for an on-road assessment, or you might elect to have an on-road assessment in a dual-controlled assessment vehicle, and what that will look like is that you're in a dual-controlled vehicle with a driving instructor in the passenger seat, and you're in the driver's seat, and a specially trained occupational therapist is sitting in the rear seat, and they are auditing your driving safety, and then they will write a report, and that report is presented back to your GP, and there are several possible outcomes from that report. So they advise your GP that you should continue to drive, sorry, or you continue to drive with certain restrictions, and these restrictions might be that you should only drive within a certain kilometre radius of where you live, or it might be that they recommend that you no longer drive at night, for example, or during rain, for example, or it might advise that driving is unsafe, and that, perhaps, you need to stop.

What I know from professional and personal experience, is that acceptance of a medical decision to stop driving is really important to that person to successfully manage the transition from no longer driving, to retiring from driving. So, what that's saying is that you have to be able to feel comfortable with that decision, and you have to be able to feel that you were fairly assessed, in order for you to accept the support, in order for you to move forward and to try out other ways of getting to your community. So, if you're someone who's supporting someone with dementia, then I believe it's important to know and to help that person to transition through that process, and to accept that decision, and to feel comfortable with that decision. Otherwise, people do get stuck in this particular phase and find it very difficult to move on. So, again, talking to key people, maybe talking to your GP about that decision and about how you feel, and helping someone come to terms with accepting that decision is very important.

It is a complex issue though in primary care, and your GP has been tasked with identifying early changes in people's memory, and so, it's usually the first person that we might present to if we're having memory difficulties, and therefore, they have been tasked with having to monitor driving issues with their patients with dementia. And they do find it a very difficult process, and they do struggle with it, and it's complicated by the fact that there are difficulties in identifying early dementia, but most importantly, they are concerned for the negative impact that that has on that doctor/patient relationship. So they feel and they tell us that they see their role as advocating for their patient's health, and they don't see it as having to police driving safety decisions, because they feel, as I said, the impact that that might have on their patients coming back to their doctor for their regular health checks, and on that relationship itself.

So, we recommend that, you maybe initiate a conversation early with your doctor, and talk to your doctor about what medical fitness to drive assessment might look like in their practise, and what that would look like for you, and acknowledge that practical and emotional loss. So, talk about what stopping driving would mean to you, what that would feel like, so that they have an understanding of how that will impact you. And you might develop a plan for retiring from driving, so involving key people in that decision making with your GP is very important as well, so taking those people along with you in that decision making process. And you might create an agreement about driving. So again, if you are able to plan this early and to create this agreement about what that might look like, what that process might look like, when you might be thinking about reducing your driving, when that person that you will trust to say to you, "Perhaps it's time to think about stopping your driving," for example. Because it can become emotionally charged for some families, it might be better, then, if you find that these conversations that you are having are quite emotionally charged, and there is conflict around perhaps the person, or the person you are supporting who's living with dementia about their driving safety.

If this happens, then two things might happen. First of all, that person who is living with dementia, the person that you are supporting, doesn't get that opportunity to talk about how they're feeling, because we tend to avoid these conversations that are emotionally charged. That person might get shut down, so if you're someone who's living with dementia, we know that it's part of therapeutic process to talk about how you're feeling. And so, the topic becomes the elephant in the room, and you don't get a chance to talk about it. So, the second thing would be, who's the right person to talk to? Keeping the lines of communication open, but if you are supporting someone through that process, and you are finding it difficult, and you're finding it too emotional for you, then find someone else, perhaps another person that might be able to lead that conversation or to involve a third party.

And what we can do as family members to help, I've touched on these already, but start a conversation about the meaning of driving. When you find out what driving means to someone, then you are able to target that support. So, is it related to their identity, their independence? Is it about getting to certain places? What is it that they value about it? And then targeting that support, addressing the feelings of loss and grief, and listening to someone's concerns, and identifying valued activities. So, what does the person that you care for, what do they want to continue to do that driving enabled them to do? And how can you help them continue to do that once they stop driving? Or if they can't continue to do that activity, can you find a substitute, and I use the word "goal", as in what's important to them? It's about getting someone out and about, and them remaining active in their community, so how can you support that? You might devise a plan of how this can be achieved, and finding supports from people around you that can help you realise that plan.

You might help with transport alternatives. Of course, you could set up a ride-sharing app, a transport card if public transport is appropriate, or finding out about taxi vouchers, and even practising alternative transport – so, going with the person that you care for and who's transitioning from driving, and practicing using Uber, or practising the taxi to and from somewhere.

You might assist with advising the local transport authority, and help find a peer support group, for example, a community café, or another retired driver that you or someone living with dementia can talk to, because we know that if you can talk to someone who's been through this process, that can be very empowering, and it can normalise some of the feelings, and some of the difficulties that you might be experiencing, but to know that you can continue to have a full and valued life without driving is really important to be able to talk to other people about that. And so, we do know that without appropriate support, the loss of driving can lead to increased risk of isolation, anxiety, and depression, and that getting out and about is important to continued quality of life, and to slowing the progression of the condition – so it's important to your cognitive health and to your health and wellbeing.

With the driving cessation intervention that we have developed, and we've been delivering to people who are living with dementia and their family members, one of the important things that we are finding, that is empowering to people is to set goals, so to talk to people who are living with dementia, and to talk to a person who's living with dementia, and understand that person's individual transport and lifestyle needs, and their values associated with driving cessation.

Again, coming back to that meaning of driving, what does driving enable them to do? And what does it mean to them? And then we set goals for helping them find valued activities helping them name their valued activities, and helping them name their goals around their needs. So, let me give you a concrete example. For example, we had a gentleman in our program who valued his attendance at a local men's shed, weekly, so they were doing a lot of really great volunteering work, and I think they were making wooden toys for the local kindergarten, and so, he was getting a lot of meaning out of his participation there, but also a lot of social support. And so, he identified that as an important goal. So, we set about helping him find ways of continuing to get to that activity once he was no longer driving. So, identifying what's important to people, and helping them achieve those goals might also mean that perhaps if they can't do everything, and if you're a person living with dementia and you do need to maybe find some substitute goals, or you might need to perhaps conserve some energy, and not do as much as you did before, it's about identifying what's really important and what you want to continue to do, and helping people get there.

In terms of adjusting to change, in conclusion, the need to restrict or to give up driving can cause significant stress if unsupported, but know that if you have the supports, and if you can plan early for eventual stopping of driving, then that is the best outcome for you and for the people around you that support you. So, providing a safe and objective environment to facilitate discussions, so we are allowing someone who is going through the process of driving cessation to talk about how they feel, and to listen to them, and to give them a voice, and to understand their needs, and to support their needs, and if you are someone living with a dementia, to keep those conversations open, to talk earlier about how you feel.

We know that it's very important to emphasise agency and dignity of the decision making, so if you are someone who is supporting someone with dementia, never make that decision without involving that person as well. Or rather, I should put it in this way, that makes sure that that decision is an involvement between all concerned parties, and talk to that person's GP alongside them. And it's very important to provide practical support as well as emotional support for the impacts of driving, but to know that by focusing on your strengths and your resources, and your personal strengths and resources, and the people around you, that you can make these adjustments, and talking to people who have been through this process before is very empowering. Thank you for listening. These are our lists of my references that I used in my talk and my contact details, and please feel free to email me if you have any questions about this presentation. Thank you.

[Title card: Together we can reshape the impact of dementia]

[Title card: Dementia Australia. 1800 100 500. Dementia.org.au]

[END of recorded material]